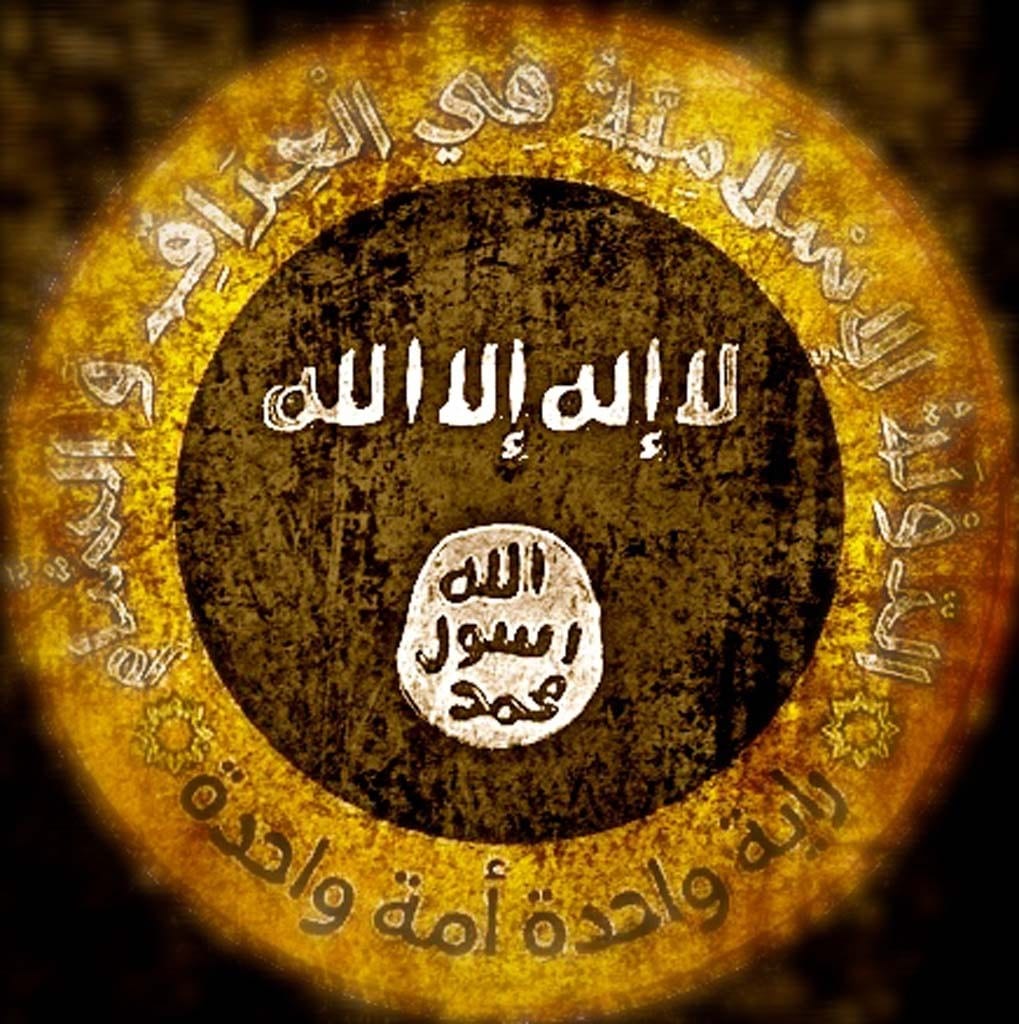

As subtle, swift, and stark as a thief in the night, the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) sprang from the ravaging badlands of Syria and inflicted a reign of terror far worse than its predecessor, Al-Qaida. A splinter-cell offshoot of Al-Qaida in Iraq (AQI) and the Al-Nusra front in Syria, ISIL forged greater numbers and strength (U.S.-aided munitions and equipment), and inevitably built up its own Caliphate of Islamic fundamentalism. ISIL intends on dominating the region of its claim by unreasonably violent means, subjecting its opponents to public executions, slavery, forced marriage, and many other abominable acts against humanity. A major adversary dismantling the prospects of a more steady and diplomatic Iraq, ISIL threatens neighboring countries and the entire international community, much like Al-Qaida, but through more contemporary methods of advertising as well (i.e. social media networks). The crisis at hand is not solely attributed to the outset of ISIL, but how exactly ISIL must be dealt with; in effect, ISIL may or may not have intended on the more unconventional battles to be waged by their enemies, but the current stratagem of the United States and Near Eastern states could unavoidably lead to triggers for multiple crises. Alliance strategies instituted by the U.S. have been key to preserving peace and stability through the security-trade nexus, but this political scheme allows for stark boundaries to be drawn between friend and foe, as the Cold War demonstrated. The lines between rival nations have blurred as the scope of ISIL’s looming dominance and influence in Iraq aggressively provokes those in religiopolitical hostility toward one another (i.e. Iran and Saudi Arabia) and those in sociopolitical opposition with one another (i.e. China, Russia, and the U.S.) to rethink their agendas in pursuit of a common enemy. The consequences of these inexorable decisions are left to be seen, but the resultant future will be that of a dauntingly transformative outcome.

America’s military budget has been reduced considerably in effort to balance a slowly recovering economy, and, consequently, troop numbers now dwindle to meet the demands of the government’s monetary adjustments. After nearly 9 years in Iraq and 13 years in Afghanistan, domestic concerns appear to be of more importance since full-fledged wars, like the initial invasions of both countries, are no longer optional in the Near East. While it may be a sound judgment among officials and their contemporaries to transition to peacetime after a decade of rotational deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan, one begs to ask whether or not President Obama’s current plan of action is the right course in defeating ISIL. Highly skilled team-based units, precision airstrikes, and coalition forces have proven themselves successful in combatting terrorism and insurgencies, but no conflict is exclusively unconventional. Advanced technology and special operations are a new dawn for American warfare, but they may be remnants of some future-past in the wake of traditional battles. Full-scale wars prompt an immediately conventional strategy that hearken to the days of old, and this will be put to the test if ISIL expands its army to impressive and threatening proportions.

Pending already tentative circumstances for the international arena, an intricate web of complicated foreign policy resolutions from multiple fronts has been woven to suppress the rise of the Islamic State. Eleven countries, one autonomous prefecture (Kurdistan), and one terrorist organization (Al-Qaida) are reassessing their motives while encountering the inescapable reality of imminent change. The Shiite-led Iraqi government is a center-point of interest for the U.S. and Iran, as America wishes to safeguard the foundation of its making while Iran is vitally obligated to Shias in Iraq. Attacking rebel groups in Syria may be the modus operandi of Bashar Al-Assad, but another prerogative of the Ba’athist Party leader parallels that of America’s priority to quash the Islamic state. The ever-wavering political affair between Egypt and Israel has come to a cooperative halt with Hamas, and the Islamic State is next on the list of targeted objectives for this longstanding, fair-weather friendship. Egypt’s militant ascendancy over the Muslim Brotherhood has put the nation at odds with the U.S., Qatar, and Turkey, but consolidation by the Islamic State poses more preemptive measures by Egypt to reaffirm their beneficiaries. Syria and Turkey, humbly acknowledging that reinforcing the Kurdish Peshmerga may be their best chance at inadvertently hindering ISIL’s progress, have momentarily set aside their fears of an enlarging Kurdistan. Qatar and Turkey are doing what they must to ensure that the Islamic movement they discretely endorsed stays as it is and does not become absorbed by the Islamic State. Though an outright antagonist toward Iran, Saudi Arabia now has a shared understanding with its rival to assist the Shiite-governed Republic of Iraq against ISIL. Labeled “far enemies” by Salafi Jihadists, the great powers of China, Russia, and the U.S., despite their own disputes with each other, maintain a strong collective awareness of disabling ISIL’s expansionist campaign. Last, but certainly not least, the U.S. and Al Qaida; the most prominent terrorist organization in recent times has firmly disassociated itself from the Islamic State, for fear of ISIL’s insurmountable brutality, and talks between America and Al Qaida have been underway.

Whether they like it or not, these powerful entities have succumbed to the dreaded status of “strange bedfellows,” in a noble yet begrudging effort to work with one another against ISIL. This seems, at first glance, to be a valiant stride for the international community, potentially gaining leverage toward long-lasting peace at the expense of terminating the Islamic State once and for all. In spite of this alluring spectacle for hope, a more probable scenario of ongoing distrust and discontent will ensnare the unlikely friendships in the well-established net of confusion. What of the Israel-U.S. alliance when Washington negotiates with Iran but allows their nuclear program to resume as a tradeoff for collaboration in Iraq? What of an Iraqi Kurdistan extending to Turkey and Syria, whereby the proposed Caliphate of ISIL, upon its desolation, territorially transitions over to the rule of the Peshmerga? What of the suspicious deals to be made between the major contenders in the Near East, Saudi Arabia and Iran? Let us not forget that most destructive of all deterrents, the WMD–could ISIL be secretly hiding what we fear most, only to unleash calamitous death on the world before losing their strength entirely? Unless another unforeseen crisis emerges from the dense fog of multilateral warfare to be waged and/or this campaign redirects itself to the solid foundation of political fault-lines that they once were, the aftermath of uncertainty appears to be most certain.

In Part 2 of ISILationism, we will touch upon the in-depth history of the Sunni-Shiite divide as a means to understand fundamental Islam and the roles to be played by Saudi Arabia and Iran in the fight against the Islamic State. Stay tuned!