Chinese president Xi Jinping has set his country’s national football team three targets to aim for: qualify for the FIFA World Cup, host it, and win it. Football has even been made compulsory in national schools, and projects for the construction of sports grounds have been passed swiftly to ensure the country can achieve its hat trick. As amusing as it may sound, Xi is by no means in the minority when he expresses his obsession and hopes for the sport. The hype over football has reached new heights, especially since the commercial success of January’s Asian Cup, a strong indicator of the game’s popularity across the continent of 4 billion.

When the national teams aren’t playing however, the majority of attention is given to overseas European football rather than local teams. Worldwide interest has skyrocketed over the past decade and a half due to weekly coverage in mass media and on social networking sites like Twitter and Facebook, connecting fans on both national and international levels to these teams. But why is European football especially popular in Asia?

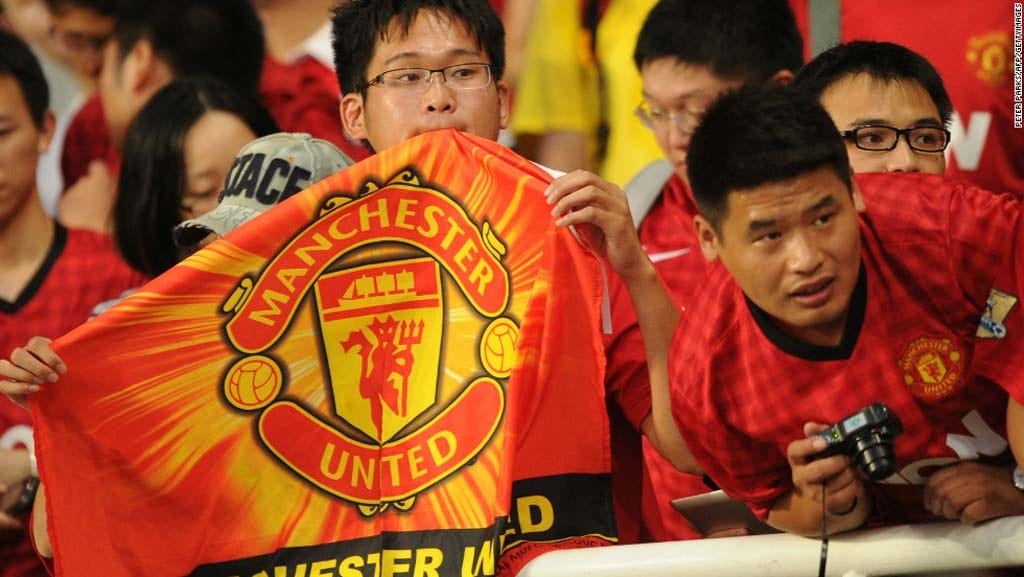

For the English Premier League alone there are an estimated 820 million supporters in Asia, according to sports research company Repucom. Manchester United claims that they have 100 million fans—and that’s just in China. Manchester City, too, has been gaining ground in recent years, with five times as many fans in Asia (16%) as there are in the U.K. (3%). This commercial success in Asia can be explained by the region’s unparalleled growth, where increasing amounts of disposable income for the growing middle class has seen greater spending on cable subscriptions and merchandise. An absence of any equivalent to major European Leagues in Asia has also made it easy for big clubs to enter Asia without much local competition.

The commercialization of the European leagues has also been triggered by the introduction of Financial Fair Play (FFP) rules, a response to clubs who were encouraged to borrow money to obtain better players and more points in their leagues, even if it meant they couldn’t break even. The Union of European Football Associations (UEFA) introduced FFP to reduce incentives to make losses, punishing clubs exceeding spending over several seasons—the most severe consequence of breaking these rules would be disqualification from European competitions. Such restrictions have motivated teams to work on their club brand overseas. With the potential for huge fan bases in Asia, it is unsurprising they are spending their summers touring Asia in friendly matches and competitions with local and even other European teams.

In Korea’s own K-League, for instance an average of 15,000 people usually attend matches. But when German team Bayer Leverkusen came for a friendly last year, the number of attendees tripled, filling the stadium—mainly due to the inclusion of “the future of Korean soccer” duo Son Heung Min and Ryo Seung Woo. It seems the patriotic streak in countries that have their nationals playing in Europe shows colorfully during these tours. Something similar happened when Manchester United toured around Asia back in 2012, where shirt sales for the only Asian on their first team, Japanese attacking midfielder Kagawa Shinji, surpassed $300 million.

What seems to be happening here is that with all the financial attention given to the big leagues, little is left for the local ones. When football can be enjoyed in the comfort of one’s home, a new angle needs to be found to win the hearts of local fans. Some sort of brain drain has also been observed with talented footballers leaving for Europe when given the opportunity, making the development of Asian leagues less sustainable. Japan’s J-League has defied this somewhat with its local competition becoming stronger even with its best players moving to Europe.

Could China reverse this trend? Its teams are being coached by old timers in Europe, and have some of the most well-paid players in the world too. On top of this, they have the opportunity to grow without the restrictions UEFA have put on European leagues. China’s own Super League has had to overcome other obstacles in recent years due to the increase in attention and investment it’s receiving from Chinese companies; match-fixing and illegal betting are rampant in the league still, and even though the government is starting to take steps to fix this (the top executives of the Football Association of China were prosecuted in 2012 for taking bribes), it remains a problem to this day.

China could very well win a World Cup before England does, (although after half a century of not winning I would argue that there really isn’t that much of an achievement in that respect,) but how it, as well as other countries in the region will reach global recognition, is a journey I, at least, am very interested in seeing the development of.