Ever since the end of the 15th century, Latin America has been seen by outsiders overwhelmingly as a place rich in natural resources. In the 21st century, the most recent outsider, China, is as hungry for its raw materials as any other previous power. It needs Argentinian agricultural products for its fisheries and pig farms to feed its growing middle class. It needs Bolivian and Peruvian iron and copper to continue building its manufacturing industries, and Ecuadorian and Venezuelan oil to fuel them. Past encounters with foreign powers in Latin America reveal a patter of resource extraction and economic dependency that benefited primarily the outside power and the local elite. Some, most notably Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro, in the region say that relations with China will be different, that China is a partner and a sister country, not an imperialist outside power. These optimists are hoping for a reinvention of the relationship between resource hungry outside powers and natural resource rich nations in the region. Unfortunately, Chinese recent forays into the region appear to be mirroring this tragic historical pattern.

In the past decade, Chinese loans to Latin American nations have reached $119 billion. To put that into some context, from 1961 to the present the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), which includes the US as one of its backers, has provided $239 billion in loans to Latin American nations. In just ten years, China has provided about half of what the IDB has in over 50. Certainly the IDB is not the only US or Western-backed source of loans to Latin America, but in recent years Chinese loans are outstripping the World Bank, the IMF and the US Export-Import Bank’s loans to the region combined.

While nominally the sources of loans emanating from the Beijing are varied, none of them are private, but instead state-owned enterprises in the form of banks or mining and petroleum companies. In essence, the Chinese government is responsible for all of the loans flowing into Latin America and all of them are part of the Chinese government’s economic plan to secure resources abroad for its internal growth. The recipients of these loans are employing using the funding to grow their resource extraction based economies. For example, Venezuela’s oil exports count for over 90% of its total exports; in Ecuador the figure is over 50%. Peru is a top-five worldwide exporter of metals like copper, gold, lead, zinc and tin, which account for over 60% of its total exports. Over a third of Argentina’s exports are agriculturally based.

Chinese raw material needs coupled with regional governments’ short-sighted extraction economies have allowed for Chinese loans to go towards projects that reinforce the economic leitmotiv of status quo in Latin America, rather than diversify. Infrastructure projects sound great, but the reality is that Chinese infrastructure loans and investment plans focus exclusively on extraction, not for improved transportation or communications for the general populace. Each nation’s interaction and trade deal with China is different and experts in the region, like Enrique Russel-Peters of the National Autonomous University of Mexico’s Center for China-Meixco Studies, have warned that analysts should not view Latin America as a cohesive or homogeneous region. Those same experts fear that China is doing just that and neither China nor Latin America as a whole has a deep enough understanding of each other’s history or present ambitions.

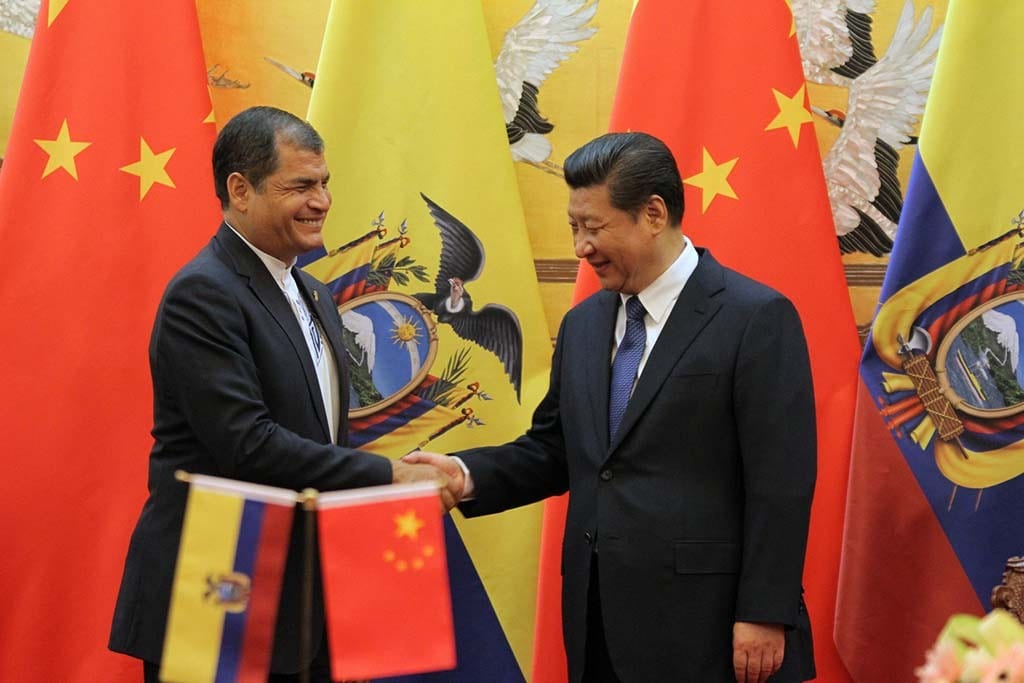

In an official statement in 2008 about its relations with Latin America and the Caribbean, China laid out an idyllic plan for peaceful development and relations with all nations. This has largely been the case with China reaching out to many nations for a variety of trade deals. It has secured free trade agreements with Chile, Costa Rica, Peru, and is currently in talks with Colombia. China has lent $119 billion to 15 Latin American nations of various political systems and leanings. At the same time, $56.3 billion or about 50% of the total loans to the region have been directed to Venezuela, home to the Bolivarian Socialist Revolution that leaders of other nations like Rafael Correa of Ecuador and Evo Morales of Bolivia also follow. Under the current President Maduro, Venezuela just received $20 billion in loans this past January. In the same month, Ecuador also received $7.5 billion in loans.

Both Venezuela and Ecuador are currently facing extreme budget gaps because of the falling price of oil and the budgetary costs associated with the social programs involved in the Bolivarian Socialist Revolution. China has come in to help plug those holes, but not without strings attached. China is contracting these loans in Yuan in order to push nations receiving the loans towards purchasing Chinese produced products. Venezuela in particular appears to be following a very Chinese path of attempting to censor both media outlets and opposition leaders. Many opposition elected mayors have recently been jailed, including the mayor of Caracas, the capital city. The sitting government blames extreme shortages of basic necessities like rice, corn meal, toilet paper, and hygienic products on US intervention and hoarding by the upper classes. In March, the Obama administration placed sanctions on the already very weak Venezuelan economy because of purported human rights violations by the Maduro government. The Ecuadorean government has also been accused of media censorship by Amnesty International. China and its closest partners in Latin America share not only economic ties but also autocratic tendencies coupled with claims to a socialist revolution.

China’s forays into Latin America are, however, by no means purely ideological in nature. Brazil is the second largest recipient of Chinese loans at some $22 billion and is recognized as a viable democracy, among many other democracies receiving Chinese loans. China appears to be practicing an economics and trade first foreign policy. However, the majority of loans are heading to regimes that use anti-American sentiment, historically justified though it may be, as a tool to discourage dissent. Latin American governments should not be choosing between China and the West as creditors and trade partners. They should instead seek the best terms from both in order to best develop and diversify their economies and truly reinvent the region’s relations to outside powers, not choose which power to depend on. China can be a partner to Latin America, but first leaders need to ensure that China’s goals and their nations’ goals are in line with one another.