In case you missed it be sure to check out the first part of the series, ISILationism, Part 1.

Beholden to the promise of containing the Islamic State, a coalition force of regional powers, such as Jordan and Saudi Arabia, has been organized under the guidance of the United States. Some onboard this multilateral feat, however, are rather questionable allies who, through one fashion or another, hold responsibility for the formation of the Islamic State! Islamists throughout the world are joining ISIL’s ranks in the Levantine expanse of bloodshed and destruction, but these are Salafi Jihadist Sunni Muslims and not one of them would be Shiite, lest they prefer suicide without geopolitical impingement. This is where Iran comes into play as the most unlikely candidate America can depend on, teetering on the paradoxical fringe of reliability and suspicion equally reciprocated by the U.S. The Islamic Republic of Iran remains adamant that their nuclear program is a peaceful means for clean, renewable energy, despite resultantly enduring sanctions over and over again without much resolve. An interim deal was made through the greater powers of the international community but, as of yet, progress has been stifled and Iran continues its plans. Nonetheless, a turning point for Iranian-American relations has been the War on Terror, whereby Iran gathered actionable intelligence on Al Qaida and jointly fostered the Northern Alliance in Afghanistan to repel the Taliban from power. Another Iran-U.S. venture in 2003 was executed in Iraq through their respective Foreign Internal Defense training exercises and the collective buildup of a representative government. Once again, Iran and America have a vested interest in the preservation and prosperity of the Iraqi government, utilizing their own drones and fighter-jets to neutralize ISIL cells through airstrikes and deploying their own special operations forces to encourage the morale of the Iraqi military, bringing the fight to the Islamic State before the usurpation of Baghdad.

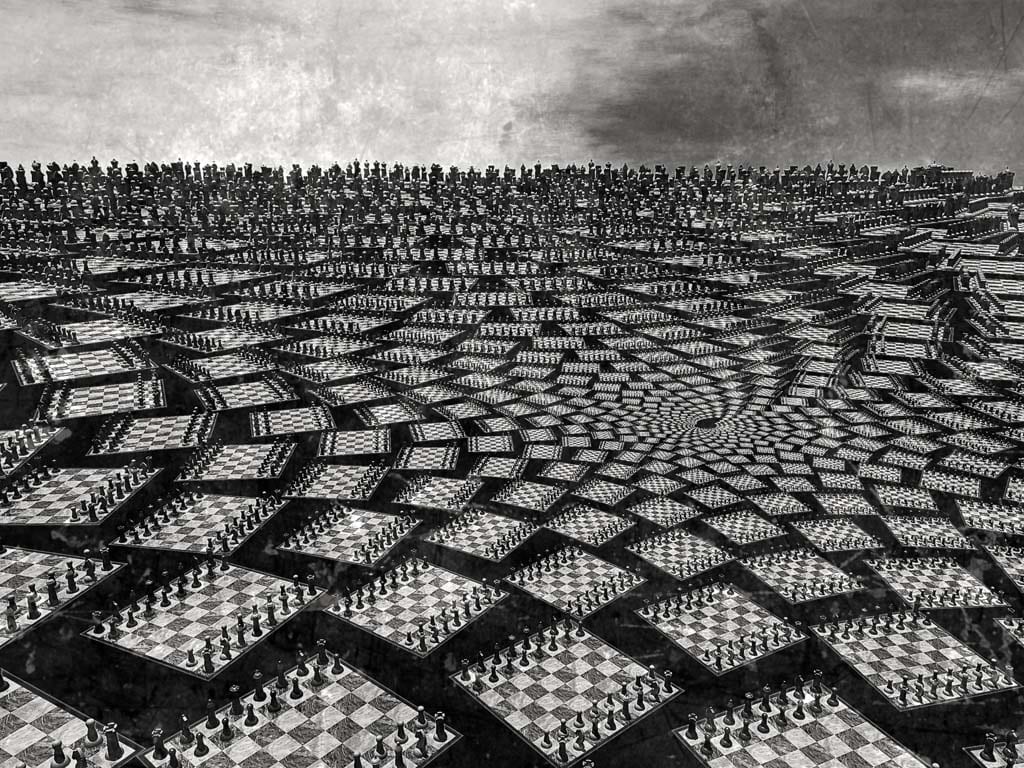

In analyzing the puzzling and chaotic nature of it all, we must first recall that much of the geopolitical demarcations and escalations of conflict in the Near East stem from the historical rift of the Sunni-Shiite divide, where even within this most salient division, the fractures grown from the split impart a complexity of ideologies foremost from the source. The epochal episodes of Sunni-on-Sunni violence and Shia-on-Shia violence lend credence to an additional sectarian obstructiveness inwardly bent and, oftentimes, domestically generated. However, on exclusively minding the Sunni-Shiite divide, Islam’s preeminent schism attests to the unrelenting pain and anguish that has marred the Muslim World for centuries, where even great political players in the international ring are still at severe odds with one another, such as Iran and Saudi Arabia. Iran is home to a significant Shiite majority and fosters an authoritarian regime rooted in Twelver Islam philosophy, while Saudi Arabia’s monarchical system lends itself to supreme authority to most of the Sunni Muslims inside and out of the Islamic homeland. Contrary to popular opinion, perhaps, Sunnis and Shias have lived just as peaceably with one another as they have lived disparately with one another, yet a newfound resurgence toward hostility between the two has launched headlong into the 21st Century. With 85% of the Islamic World following Sunni orthodoxy, the roughly 15% of Shia adherents have suffered outright victimhood since the beginning of the Sunni-Shiite divide long ago. Although the current predicaments faced by Shias is intimately rooted in the historicity of Islam, it would be pertinent to observe more modern accounts attributed to the socio-religious, inter-political rift occurring specifically in Syria and Iraq. One not need look too far, however, to notice the clerical supremacy of the Ayatollah in Iran and the royally approved Wahhabism promoted by Saudi Arabia.

Iran’s Islamic Revolution of 1979 set the stage for a renewed peak in sectarian violence lasting until now, propelled by the aggressiveness of both sides to secure their respectful interpretations of Islam. Since then, regional states have been fraught with native religious discord borne from the divisive tensions of Iran and Saudi Arabia. Roughly half of the Sunni population accepts Shias as true Muslims, while the other portion rejects them. This animosity is instigated and ultimately propagated by the antagonism of Wahhabism in Saudi Arabia. The threat of ISIL’s expansion and wide-ranging influence on sectarian oppositions throughout the Near East may, in fact, compel a peaceful unison of Shias and Sunnis to thwart the Islamic State. On the other hand, regardless of however extreme each faction may be, these events may also be dependent on whether or not the following is true: that the relative gains of Sunni belonging versus Shia belonging could easily foster the terms of anarchistic self-preservation from both fronts. In short, ISIL might incite those outside of its camp to drop their differences and strife with one another in order to mutually prevent their own future demise; contrarily, the feasible bandwagon of zealotry could, under the extreme climate of ongoing unrest, throw the Near East into an aggrandized religious war with transnational implications beyond anything we have witnessed so far.

The Islamic Republic of Iran may surpass the Syrian regime, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, and even the Kurdish Peshmerga as America’s most conspicuous hopeful in conquering the Islamic State without many U.S. casualties. Unfortunately, the pure and utter animosity among Syria, Saudi Arabia, and Iran is, itself, an issue of stalemate not ill-acknowledged by the U.S. All things considered, the Kurdish Peshmerga still appears to be America’s most realistic and reliable counterpart on the ground in Iraq. Saudi Arabia is a trusted source for the U.S., but the willful progression of Wahhabism and localized Sunni fundamentalism places Saudi Arabia on the side of ambiguity. Iran is an overtly designated enemy of the United States, but the Iranian Shiites are just as committed to bringing down ISIL as the Kurdish and American forces. President Bashar Al-Assad may be a war criminal and a brutal leader, but with the backing of the U.S. and Iran the Islamic State will struggle within its own squander if all the cards are played right. Yet, why is the U.S. so implicit in its stance to attack from afar and through transparency (i.e. airstrikes, special operations forces, etc.) while entrusting the Iranian-backed Iraqi government and Kurdish Peshmerga to do all the dirty work?

In Part 3 of ISILationism, we will focus more on America and Syria’s involvement, the origin of ISIL, and the questionable end-game scenario for the Islamic State. Stay tuned!