After COP21: Mexico In-Between Energy Security and Climate Change Mitigation

Climate change is perhaps one of the thorniest economic and social problems of our time. This is not unrelated to the fact that in many countries, the forms of energy that power economic growth are those with the highest concentrations of carbon –oil and coal. It has been argued that it only takes three economies – the United States, China and India – to produce more than 40% of all global greenhouse gas emissions [1]. After the recent UN Paris Climate Change Conference (COP21) nonetheless, energy policies have quickly become priority issues in many developing countries’ agendas for a number of reasons, ranging from new technological developments and economic benefits to above all, energy security and climate change mitigation. A number of technical and economic challenges are likely to emerge in the near future, given the widespread development of fossil fuel resources and their incompatibility with decarbonised energy systems, now being adopted across many of these regions to mitigate global climate change.

Europe’s Migrant Crisis – of the 5th Century

Rome was not built in a day, the saying goes. Yet the idea of a rapid “fall of Rome” seems to be commonly accepted: non-Roman barbarian “others,” taking advantage of Roman weakness, pouring across the borders and tearing down civilization, leaving Europe in a cultural backwater for the next millennium. This is an image which easily captures the imagination, and it fits into the general narrative of the Middle Ages as a generally backward, barbaric era. It has unrelentingly maintained its grip on minds, child and adult alike, even over the protests of professional historians who frown upon the use of that demeaning, and inaccurate, term “the Dark Ages.” Such a pessimistic view of an entire thousand plus years of European history is in fact the result of successful propaganda by Renaissance-era thinkers, who sought to emphasize their achievements by contrasting their time period with the alleged barbarism and darkness of the centuries before them and signaling a return to the cultural and intellectual glory of classical Europe (hence a “rebirth”). And the beginning of all the darkness of the Middle Ages begins with the so-called “fall of Rome,” precipitated by the mass movements of barbarian tribes who allegedly did not adhere to “Roman ways” and ended up destroying the empire.

But the real question that needs to be asked is not “why did Rome fall?” but rather “did Rome fall at all?” And the argument can be convincingly made that it did not, in fact. Rather, the migrations that took place between the fifth to the eighth centuries across Europe should not be seen as “barbarian invasions” but rather the incorporation of diverse (not just a monolithic “Germanic tribe”) peoples on the periphery into the Roman world. Rome never “fell” – it was instead fundamentally changed by the active participation of people on both sides of the borders, including the Roman authorities themselves, who used techniques from land distribution to tax shares.

But the idea of the “fall of Rome” is difficult to let go. The tragedy of the fall of a cultured civilization makes for a good story charged with pathos. And, perhaps more importantly, the narrative speaks to many contemporary fears of the “other” and the dangers that mass migrations are deemed to pose to one’s own society. Rather than offering a direct instructive example, of course, history is said to teach by analogy, and perhaps in a related vein of thought, we need to be wary of the images we hold about mass migrations and movements of people across borders. The recent tragedy in Paris has increased scrutiny on the refugees entering into Europe and sparked debates about their identity. The terms used in such discussions are politically charged. In referring to the ongoing events, media reports split on their use of either “migrant crisis” or “refugee crisis.” These terms, though to the unsuspecting may initially seem interchangeable, reveal a deeper, serious disagreement over the nature of the people who are coming into Europe: are they migrants, a more general term that may also refer to those seeking better economic conditions to improve their livelihoods, or are they refugees, fleeing persecution and bodily harm in their home countries? For the xenophobic elements, of course, the distinction is not important – whether migrant or refugee, they pose a threat to Europe and need to be kept out.

But those that seek to preserve some idea of a pure and original “Europe” against an alleged threat from immigrants and refugees are deeply misled, and an attempt to “keep them out” is both infeasible and bound to be fruitless. Movements of people across countries, across borders, across any space, are some of the most powerful forces driving history, helping to promote cross-cultural contacts, innovation, and political, economic, and societal developments. The movements in Europe in the fifth through to the eighth centuries did not destroy the civilized world and Roman culture—rather, it brought large groups of people in greater contact with one another and fundamentally altered the face of Western Europe.

Contrary to the Renaissance view, the Middle Ages saw the rise of universities as we know them today, the development of what would become our modern-day Romance languages, and vibrant advances in art and architecture that we can still admire. This is certainly not to whitewash the darker aspects of the period, in which some historians see the beginnings of Europe as a persecuting society, targeting not only Muslims and Jews but also Christian religious minorities, lepers, and homosexuals.

But even as we note and decry these aspects, we should be careful not to descend into the condescending attitude towards the past that characterized Renaissance views of earlier centuries and that still remains with us today – the notion that somehow we in our own time period are so evolved and intelligent that we have the right to sneer on the obvious stupidity of those that came before us. Considering the xenophobic and racist parties across Europe gaining greater ground, state governors in the U.S. declaring that they will refuse to accept any refugees, and the many instances of systematic oppression around the world, it is not apparent that we ourselves are any better. We should be so lucky to not be harshly judged by our descendants as being on the wrong side of history.

Cyclical Failure – Economic Crisis and Commodities in Latin America

Despite a great deal of discussion on the information economy in recent years, (much of it useful and much of it overhyped,) the actual world economy’s health is still reliant on raw materials, which is expressed in their prices. While in parts of the developed world the recent fall in commodity prices has been referred to as the equivalent of a tax break, in countries that are heavily dependent on commodity exports, calamity is a better reference point. The primary issue here is dependence. Many developed nations also produce raw materials in great quantities, but their economies are comparatively diverse. When a nation’s basket of exports is dominated by just a few commodities while its import basket is varied, economic crises are more likely to occur.

The Will of the State: North Korean Forced Labour

The 2014 report of the United Nations Commission of Inquiry on human rights in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) laid bare an appalling scale of suffering across North Korean society. Violations of the freedoms of thought and life, discrimination on the basis of gender and disability, and arbitrary detention, torture, and executions defined the lives of a population. A report of the European Alliance for Human Rights in North Korea (EAHRNK) that we published in September 2015, ‘The Will of the State: North Korean Forced Labour’, places forced labour alongside these crimes against humanity.

Energy Reforms in Latin America: What the Mexican State Needs to Learn

The growing importance of developing countries’ national oil companies to the global supply-demand balance raises questions about the emerging policies of association, objectives and regulations of these organisations. In particular, shifts in those policies will have a great impact on the future development of global oil and gas markets, not to mention the socioeconomic development of the companies’ host countries.

National oil companies are expected to control a greater proportion of future oil and gas supplies over the next two decades, as these commodities in the mature producing regions of the OECD countries continue to show natural decline of supply. The International Energy Agency projects that most of the new hydrocarbons supply will come from the developing world in the next 20 years. Latin American countries will play a pivotal role in this transition, as the region possesses more than 20% of the world’s known reserves (Ortiz, 2011). Along these lines, Brazil, Colombia and recently Mexico have embarked on major restructuring of their energy sectors.

In the early 2000s, the Colombian oil industry was waning: its production started to decline due to a lack of major new discoveries and output fell considerably from 1999 to 2004 (CAEAG, 2010, p. 6). The Colombian government remained dependent on its national oil company, Ecopetrol. In 2003 however, Colombian President Alvaro Uribe initiated a process of liberalisation and privatisation of the industry, and by 2006, his government created a mixed-system public company (CAEAG, 2010, p. 6). These reforms were modelled in part after a set of reforms that had begun in Brazil during the late 1990s that opened up the energy sector to private capital and participation of international companies while the state maintained partial control of Petrobras (Fuentes & Rico, 2014, p. 33).

Before 2013, Mexico’s oil industry stood in a similar state of decline like that of Colombia prior to liberalisation. The model of production in Mexico lost its effectiveness in terms of its regulatory and organisational structures. Moreover, the model was unable to meet international and even national expectations of supply and performance due to a lack of technology. Once considered as one of the top ten crude oil producers in the world with the highest output of 3.5 million barrels per day (bpd) in 2004 (Baker Institute, 2011), Mexico’s recent production of less than 2.5 million bpd (Sen & Upadhyaya, 2014, p. 3) triggered a series of political debates concerning the future of energy security and the imperativeness to restructure the industry.

As in Colombia, the problem in Mexico did not lie in a lack of resources, but rather in the lack of capital and regulation. The roots that bind the Mexican oil company Petroleos Mexicanos (PEMEX) and the country’s government run even deeper than those that once bound Ecopetrol and the Colombian government. PEMEX was traditionally not only the most important company in Mexico as it used to pay approximately 40% of the state budget through taxes (CAEAG, 2014, p. 9), but also was involved in the three most important activities of the national oil industry: policy making, regulation, and operation of resource exploitation.

However, with the 2013 energy reform, foundational transformations were designed to be implemented in the Mexican hydrocarbons sector. According to the country’s Ministry of Energy, policy makers formulated the latest energy reform based on the institutional design of the Colombian and Brazilian energy sectors, whose reforms resulted in annual growth rates in oil production of 6.4% in Colombia and 6.3% in Brazil respectively (Leon et al., 2014, p. 6). The Mexican energy reform would not only help restore the country’s ailing hydrocarbons sector, but improve its competitiveness in the global markets, develop new infrastructure, and even improve welfare delivery for Mexicans as public sector revenues are supposed to increase.

Other reasons that have motivated changes in the Mexican energy sector include the need to restructure the role of the state after 77 years of the inefficient, monopolised industry and encourage public-private partnerships in areas of exploration and production. The Ministry of Finance will no longer control Pemex’s budget and the Administrative Board will be reduced to 10 members (Mexico’s Energy Reform, 2014, p. 17). Even though Pemex will change from a decentralized public entity to a state productive company, it will continue to play a strategically important role in the Mexican economy and for the public sector. It is projected that the first hydrocarbons production, under the new Mexican law, will begin in a time-frame of 10 years, and therefore policy makers are expecting the Ministry of Energy and the regulatory agencies to experience a learning curve during this initial period (Bueno, 2014).

The new statute in Mexico has the potential to open immense new investment opportunities for foreign and national companies, although the first tender in the bidding process of oil fields in the Gulf of Mexico deep waters, known as “Round One” in July of this year, was not so successful. However, challenges go well beyond the more limited priority of attracting direct foreign investment to the sector. The Mexican energy reform promotes privatisation, deregulation, and market strategies to deliver services — once a state-exclusive realm —, yet it also advocates for protectionism and preferentialism for PEMEX in bidding. It decries government intervention yet still operates through political influence. It claims that its central goal is to increase national control over the unexplored oil and gas resources, yet it will coordinate complex alliances with private oil multinationals, banks and international agreements of supply with other countries. Hence, the success of this venture is in part dependent on improved regulation and accountability within the Mexican energy industry.

The participation of other actors in the administration and implementation of policies in the sector suggests the ‘the hollowing out state’, characterised by the breakdown of bureaucracies and the increasing competition among bidding companies. As a result, this leadership renovation of the public implies more governance and less government, among other things. Some critics would define it as the greatest detachment from politics, or a fragmentation of political authority, where the state’s capacities are being reduced as well due to a displacement of power. The state’s power will slowly move towards multinational economic agencies and private organizations, where the markets are prone to set the rules of the game.

The introduction of pro-market energy reforms in Mexico, Brazil, and Colombia implies a shift from vertical hierarchies, as the principal method of controlling state-owned companies, to collaborative arrangements. Closer cooperation between public and private sectors produces both strengths and weaknesses in the management and flow of information. On the one hand, partnerships assume that through a more intensive collaboration between public and private sectors in sharing risks, costs and profits, better and more efficient outcomes can be realised for the state. On the other hand, collaboration may cause a lack of both accountability and enforcement, in which the flow of information between actors of the energy sector and citizens becomes obfuscated and thus circumscribed.

Having said that, regulation and accountability remain as major challenges in the area of liberalised energy sectors. It is noteworthy that in the midst of the liberalisation of government operations, there is an inclination to increase and strengthen public accountability mechanisms. Therefore, the Mexican state should fund and empower the energy sector regulators accordingly to the size of this promising venture, learn from international experience and keep up with markets dynamics, thus avoiding what might become just a costly experiment.

Bibliography

Bueno, J. (2014). Companies are coming to get profits but we will stop them: Bueno Torio (Interview in Spanish). Aristiegui News. Retrieved September 9, 2014, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s9x6DoHoduM.

Ortiz, G. (2011). Latin America Holds One Fifth of World’s Oil. Inter Press News Agency. Retrieved April 16, 2015, from http://www.ipsnews.net/2011/07/latin-america-has-one-fifth-of-global-oil-reserves/

CAEAG. (2010). Colombia’s Energy Renaissance. Americas Society/Council of the Americas Energy Action Group. Retrieved March 20, 2015, from http://www.as-coa.org/sites/default/files/ColombiasEnergyRenaissance.pdf

Manzano, O., & Monaldi, F. (2008). The Political Economy of Oil Production in Latin America. Economia, 9(1), 59-98.

Baker Institute. (2011). Mexico Could Become Oil Importer by 2020. Oil & Gas Journal. Baker Institute Policy Report. Retrieved March 1, 2015, from http://www.ogj.com/articles/print/volume-109/issue-20/general-Interest/baker-institute-mexico-could-become-oil-importer.html

Sen, A., & Upadhyaya, S. (2014). Awaiting the Mexican Wave: Challenges to energy reforms and raising oil output. The Oxford Institute for Energy Studies. Retrieved June 30, 2015, from http://www.oxfordenergy.org/2014/06/awaiting-the-mexican-wave-challenges-to-energy-reforms-and-raising-oil-output/

CAEAG. (2014). Mexico: An opening for Energy Reform. Council of the Americas Energy Action Group. Americas Society/Council of the Americas Energy Action Group. Retrieved March 20, 2015, from http://www.as-coa.org/sites/default/files/MexicoEnergyReport2014.pdf

Fuentes, R., & Rico, D. (2008). Oil in Mexico: Pozo de Pasiones. The Energy Reform in Mexico Debate. Wilson Centre Mexico Institute. Retrieved January 20, 2015, from http://www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/oil-mexico-pozo-de-pasiones

SENER. (2014). Round Zero. Secretaría de Energía. Mexico’s Ministry of Energy. Retrieved August 24, 2015, from http://sener.gob.mx/webSener/rondacero/_doc/Round%20Zero.pdf

Leon, E., Martén, I., Livas, R., & Mereles, M. (2014). The Promise of Mexico’s Energy Reform. The Boston Consulting Group. Retrieved December 24, 2014, from http://structura.com.mx/-/downloads/ThePromiseofMexicosEnergyReforms.pdf.

Villiers, D. (2014). Mexico’s Energy Reforms Become Law. Brookings. Retrieved February 15, 2015, from http://www.brookings.edu/research/articles/2014/08/14-mexico-energy-law-negroponte#_ftn2

Rhodes, R.A.W. (1994). The Hollowing Out of the State: The Changing Nature of Public Service in Britain. The Political Quarterly, 65(2), 138-151.

BBC News. (2015). Petrobras corruption costs hit $2bn. BBC. Retrieved April 20, 2015, from http://www.bbc.com/news/business-32422875

O&GJ. (2015). Three blocks awarded in Mexico’s Round One second tender. Oil & Gas Journal. Retrieved October 25, 2015, from http://www.ogj.com/articles/2015/09/three-blocks-awarded-in-mexico-s-round-1-second-tender.html

Moves to a Service-Based Economy is Likely China’s Catch-22

The achievements of President Xi Jinping’s short duration in Britain are the first steps of what China hopes to be the path to becoming a fully-developed country. Proclaimed a “golden era” in relations between the two nations by Prime Minister David Cameron, China views Britain as a “great platform from which China can go global,” according to head of Chatham House’s Robin Niblett.

Indeed, as China seeks to shift its economy from an export-based to a service-based economy and to propel the yuan into an internationally-traded currency that could potentially rival the dollar, yen, and Euro, access to Britain’s financial markets is viewed as critically important after the conspicuous blockade from the Trans-Pacific Partnership by the United States.

Outside of Hong Kong, as President Xi told the British Parliament, the United Kingdom is the leading offshore trading center. As The Economist notes, “The Bank of England was the first G7 central bank to sign a swap agreement with China’s central bank.” Offshore yuan-denominated bonds were recently sold in the UK by Chinese commercial banks and on October 20th, China sold its first sovereign bond worth over $4 billion in London. What this accomplishes is that it lends an air of credibility to the Chinese yuan as an international currency. Britain was also the first major Western power to step on board the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank led by China.

American politicians will need to find new ammunition as China cuts ties with its mercantilist policies. Long a punching bag for Trump, Webb, Romney, and others, China’s export-led growth gained what many call an unfair advantage in global markets as China often intervenes to prevent rapid appreciation of the yuan against the dollar. A strengthening yuan hurts Chinese exports and lowers the income level of Chinese exporters in markets that trade in dollars. At six yuan to the dollar, a t-shirt exporter from China who generates $100 per day in revenue receives 600 yuan. A stronger yuan means it takes less yuan to purchase a dollar (or more dollars to purchase a yuan). At three yuan to the dollar, the same amount of t-shirts generating $100 a day now only brings the Chinese business person 300 yuan a day. In order to prop up its exports, China currently employs a strategy of intervening in markets by purchasing enormous amounts of dollar-denominated reserves which artificially increases the value of the dollar by driving up demand and simultaneously decreases the value of the yuan by increasing the supply. This has largely been China’s policy over the past several decades whenever the yuan drifted outside of its desired peg range.

This will change as China moves its economy away from low-cost labor and manufacturing and more towards sophisticated services. China recently drafted its 13th five-year plan for its economy. Though it once set production measures for steel, grain, and other manufactured goods, the role of the plan started to relax in the 1980s as China shifted away from a command economy. The five-year plan won’t be unveiled until March, but in a communique released at the end of the plenum, Xinhua announced that in addition to moving the economy away from heavy industries and towards consumption and services, there will also be an emphasis on promoting and incentivizing innovation along with a pledge to reduce the frequency of state intervention in the market.

This may be viewed with skepticism as China recently pumped $200 billion dollars into its economy following severe stock market declines this past summer. President Xi has also publicly stated that state-owned-enterprises will continue to play a dominant role. Yet, history has shown that banks have traditionally granted capital to industries the plan aims to develop, while both state-owned and private firms adjust their business goals accordingly. This further underscores the importance of China’s new-found relationship with Britain. The Economist points out that the rebalancing of China’s economy will likely “play to Britain’s competitive advantages in sectors like education, high-end engineering and scientific research.” These are all components necessary in an economy emphasizing services. President Xi even made a stop at Imperial College London which announced new education and research collaborations with China. The innovation of science and technology comes about with research and education—both points of emphasis in the communique from Xinhua.

With a trade deficit with China of $340 billion in 2014, this should come as good news for American exporters who feel China unfairly manipulates its currency to give its exporters a competitive edge. Indeed, the trade deficit with China has steadily increased from only $6 million in 1985 to over $33 billion in 1995, $200 billion in 2005, and is currently on pace to surpass $350 billion in 2015. Expect to see these figures plummet as China will necessarily need to allow the yuan to liberalize as China makes the move to a service-oriented economy. With a declining emphasis on exports, there will no longer be a need for the People’s Bank of China to intervene to keep the yuan within its current peg range. China will also want to see the value of the yuan appreciate if there is any hope of it becoming an international currency. A strong, international yuan makes US exports more competitive and a Chinese economy focusing on services such as education, science, and research will continue to raise China’s national income per capita.

For all the pomp and circumstance surrounding President Xi’s visit to Britain and the future of China’s economy, there are also a fair amount of voices aiming criticisms at the authoritarian state’s human rights record. Liu Xiaobo is currently serving an 11-year prison sentence for “subversion of state power” for his involvement with Charter 08, a manifesto calling for pluralist politics in China. Ironically, it is the same work he contributed to Charter 08 that won him the Nobel Peace Prize in 2010. Tibetan monks can be jailed for simply talking to foreign journalists about the Dalai Lama. While democracy is not necessarily a precondition for economic development, economic growth does often lead to the establishment of democratic regimes. A number of Asia’s fastest growing economies, including Taiwan and South Korea, adopted democratic governments after the emergence of a burgeoning middle class. Though the Communist Party of China will never admit it, we already see this happening in China with its landmark decision to end its decades-long one-child policy, a move that McClatchy DC calls an acknowledgement that the policy hinders economic growth.

With couples preferring boys over girls in a system that only allows one child, a gender imbalance has emerged that will lead to 30 million more males than females within the next five years in China. As Stuart Leavenworth notes, this is a “formula for potential unrest and chaos of the kind party leaders fear most.” In an effort to curb the potential for political unrest and simultaneously reverse the trend of a shrinking working-age population, China has unintentionally catalyzed its progress towards human rights reform. Though single women are still barred from giving birth, the fact that the state is retreating from a draconian population-control policy further illustrates how economic development creates pressures for individual freedom and liberties.

Economic progress in China signals economic prosperity in Britain, the United States, and beyond, and also potential for the advancement of human rights in the world’s largest totalitarian state. The internationalization of the yuan born from a service-based Chinese economy is a win-win for everybody.

Poland Shocks The Visegrad Group: An Uncertain Future For The V4

The Visegrad Group (V4) made up of Poland, Slovakia, The Czech Republic and Hungary are an often overlooked bloc of Central European powers. Originally a “triangle” of Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary created in 1991 after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the now four members (after 1993) of the Visegrad Group have worked together with various degrees of closeness and success. Originally set with the task of developing capitalist and democratic institutions in the post-Soviet era, the largely informal meetings between the V4 countries helped achieve remarkable results for countries who had until then stagnated under the Soviet system. Following this success, it was no surprise when the raison d’être of the group shifted towards joining NATO (1999 except for Slovakia in 2004) and the EU (2004), further integrating the former Soviet countries into the larger European system. Now integrated into a well established institutional political framework, the members of the V4 no longer had much reason for the Visegrad Group. Indeed, the ethnic and linguistic differences between the Slavic Poles, Czechs, and Slovaks with the Hungarians means that little cultural unity existed beyond a shared bond of Soviet-subjugation. Then perhaps unsurprisingly it was Russia’s response to the Orange Revolution in Ukraine and the worrying trajectory of a resurgent Russia, such as the Georgian-Russian Conflict in 2008, that may have kept the drifting Visegrad Group together if only due to a doubt of the robustness of NATO. In addition, the experience of the V4 countries within the EU where they were more often than not viewed as an afterthought by the Western European powers meant that some sort of Central European unity would not be without merit if only to symbolically strengthen the region’s stature within the EU.

Indeed it seemed that up until earlier this month the prospects of a reinvigorated V4 taking center stage looked bright. The Visegrad Battle Group, led by Poland and in concert with Ukraine, appeared motivated and ready to act as a permanent unit after 2016. This Battle Group presented numerous opportunities for the V4 countries, including the ability to increase cooperation between the states and to increase their prestige in Europe by demonstrating their utility to NATO. The ability for the Battle Group to sustain itself is particularly important as it forces Poland to take a leadership role it has been growing into but long been reluctant to fully embrace in both the V4 and Europe. It also hopefully serves to align the differing perceptions of “threats” of the V4 members, in particular the view towards Russia with which Hungary has had warmer relations than the other V4 countries. The outbreak of the migrant crisis towards Europe also presented a rare opportunity for the Visegrad Group to assert itself as the members where uniformly against the proposed quotas dictated by Germany through the EU and in a rare showing were unafraid to speak up. Slovakia’s Prime Minister Robert Fico has called the quotas “irrational” and that during his term “mandatory quotas will not be implemented on Slovak territory“. Czech Prime Minister Bohuslav Sobotka called for an end to the “unproductive debate on a mandatory distribution mechanism for refugees, which is not the right solution, and instead to implement measures leading to a real solution to this crisis as fast as possible.” It appeared that an issue to stir the V4 to decisive action had arrived. On the eve of a meeting of an EU Summit on the migrant crisis in Brussels where the topic of quotas was set to take center stage, the Visegrad Group reaffirmed their common position decided earlier in Prague on September 4th and issued a joint statement outlining their combined objectives in response to the developing migrant crisis. For a group of countries that had been historically an afterthought and not considered seriously by other EU member states, this appeared to be a galvanizing moment that would hopefully finally strike life into the V4 members and strengthen the bloc.

However, during the meeting and in a stunning backtrack of statements just hours before, Warsaw voted for the proposed quotas. The fallout domestically was immediate and Polish politicians scrambled to explain their position to a population wary of foreign migrants. Internationally, the move shattered the credibility the V4 had gathered up to then as it was once again demonstrated to the other European States that the V4 could not “walk the walk” and did nothing to change the perception that the individual states had meddling influence within the EU. For Poland in particular it was once again a missed opportunity to show independent leadership and assert its growing position in Europe as it once again showed a deference to Berlin. The best justification Poland could offer was effectively a shrugging of the shoulders when Piotr Stachanczyk from the Ministry of Immigration said, “We couldn’t have blocked the [EU] Council decision even if we were four. We could have said ‘No’ and had no say in the negotiations, or we could have done what we did”. In the fallout following the voting and having lost the unifying power of Poland the other V4 members quickly took on differing paths. Hungarian Prime Minister Vikor Orban has confirmed old suspicions and signaled a move to get closer to Russia to address the migrant crisis while also resuming the bellicose war of words with Brussels and Berlin. Slovakia and the Czech Republic similarly have moved closer to Austria who also shares an opposition for the intake of Middle Eastern migrants.

While these independent moves by Hungary, Slovakia and the Czech Republic may play well to their domestic constituents in the short term it is only a paper victory. Without any real unity, of which an independent Poland is the cornerstone, the individual countries and their citizens have little hope of having their voice be more than a passing concern in the ongoing migrant crisis. On its current trajectory Hungary will continue to alienate allies and any attempts to unilaterally build a wall to stop the tide will be futile as Berlin has clearly indicated by its inaction in tackling border security that it intends to continue to welcome more migrants in the future. Slovakia and the Czech Republic also will find that ultimately they are much more dependent on Berlin and Brussels than these European capitals are on them and will have to capitulate to accepting the imposed quotas. This may ultimately lead to further suspicion and distrust within the EU as well, already the two fundamental planks of the EU (the common currency and the Schengen Zone) have been challenged in recent years. The continued casual dismissal of the very real and founded concerns of a growing part of the EU by the “old guard” will do little to inspire the bailout-adverse Slovakia or the Euro-sceptic Poland and Czech Republic or a Hungary that seems to instigate confrontation. Most recently Romania also has voiced its concerns and spoken out against the way the decision was made. While the Visegrad Group will hopefully learn from the EU Summit and continue to exist into the future, the past September unfortunately remains just another missed opportunity for the V4 and the members themselves to finally assert themselves as equal partners in European politics.

Beacons Over Mars

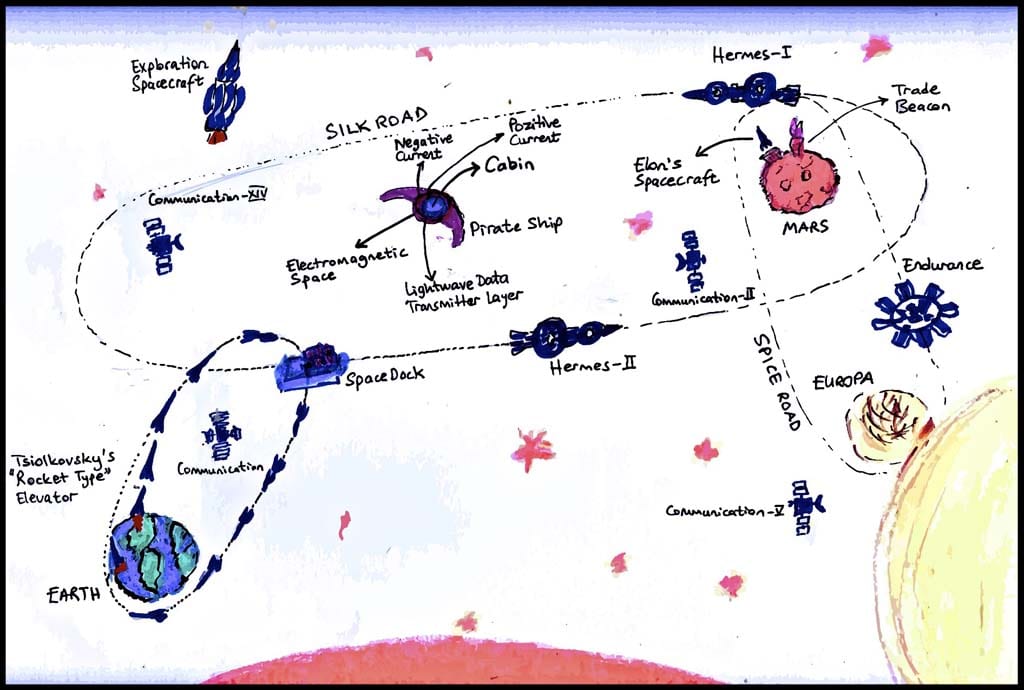

Lets begin with a question: How is trade created? At first an intellectual being defines a phenomenon and then that person (or maybe someone else who has somehow acquired that knowledge) generates an interest for it. Spontaneously that interest defines a need which ends up with an exchange. The difficulty of this process can vary; sometimes rocket science is required to define a phenomenon but sometimes it is as easy as lighting a beacon. For instance the Silk Road of the ancient world was not even a leveled sand road but rather several beacons lit by the locals to invite trade caravans. As a result goods, science and culture were transported to both ends of the known world, forming our past. It is of course a fact of history that trade has not only created immeasurable wealth but also caused devastating wars. Some countries boosted their intellectual capacity and flourished whereas some regions ended up covered by sand plagued by chronic instability. That’s why we read about geopolitics in our daily lives. History gave us a great example when colonialism overturned the existing Central Asian and Middle Eastern status-quo causing the wealth of European Empires’ to be revolutionary in every aspect at the expensive of others. The time of the Middle East has already past. Their phenomena are over. Unfortunately losing economic importance not only takes away wealth but also erodes the science and the culture of the nation; triggering inevitable decay (a deadly loop). Regrettably I cannot envision any possible scenario to change their fate to come back to life.

The Silk Road, British – Indian Spice Trade Route and the Trans Pacific… Where will tomorrow’s caravans go? For how long are we still going to discuss the rise of China? More likely humanity’s next beacon will be in space and we will see a similar revolutionary change comparable to the discovery of the Cape of Good Hope. Partially due to the size of such a venture, any central-planned organization or government alone cannot bear the cost this type of space program. Even NASA requires more partners because simply it cannot afford an Apollo-like-run mission. Interestingly, privatization of orbital travel appears to share similarities with 16th-19th century British and Dutch companies pursuing trade. Risk sharing, law making and all other related terms are returning to our daily vocabulary. NASA’s involvement with private companies like SpaceX is well illustrated in mainstream pop culture such as 20th Century Fox’s movie The Martian. Whether astronauts discover any valuable resources or not, the next trade beacon paradigm will be in space. Likely the nation states won’t be Spain, Portugal, the Kingdom of England and Netherlands but rather the US, China, Europe, Russia, India and Japan (maybe even others). However the US seems likely to be the major stakeholder.

What if Jupiter’s moon Europa will be the next step after Mars? Can the minor stakeholders follow up the US (maybe we will start calling the United States something else after they make several successful discoveries)? Will the remaining nations who have not achieved success enter in to the same unfortunate deadly decay? What if there will be several ships as the Martian’s Hermes (which looks more feasible than my humble electromagnetic pirate ship illustration) orbiting between Mars and Earth docking cargo? Does it sound utopic?

Maybe the US’ next president will follow up budget cutting policies and delay the space program. It is likely though that despite whatever cuts made to NASA’s budget mankind’s orbital travel will continue to follow a strategy similar to the Stackelberg leadership model, where NASA and its partners are the leaders and the rest of the world followers. Clearly the US is using space discovery in its politics and diplomacy. It is empowering local firms like SpaceX, Boeing, SNC and Lockheed Martin when executing decisions over Roscosmos and German car producers (referring to the Obama Administration’s cancellation of missions like the Baikonur Cosmodrome and also the timing of actions related to German car producers such as the VW). Thus whether or not space is again being used as a political cover for ongoing behind the scenes conflict between Russia and NATO allies, a step ahead for all nations is not going to be local at the country level action; it is going to be in an interplanetary level. It will be reflected in our stock markets and our diplomacy discussions. Therefore countries are approaching a critical time to have serious discussions about their future. For the sake of their personal success they should renovate their fundamental approaches to politics, diplomacy, economics, education and science. Policymakers should coordinate with their residents to prepare for the next paradigm shift. Educators should completely restructure the approach of education to encourage creativity and innovation. Otherwise they cannot even hope to be the “followers” in the Stackelberg model, left with nothing remaining on the poker table to collect. As a case in point, clearly we are not talking much about successful old civilisations such as Uzbekistan. And what about where we started this process, the Middle East, the historical pioneer of trade? Let’s hope it will achieve things other than being a martian movie set! Otherwise it will be nothing more than sand and shadows.

“Trade Routes of the Future” illustration by the author.

Do Economic Sanctions Work? The Answer is Still No.

With the seeming success of sanctions in Iran and the end of similar measures against Cuba, the debate on the efficacy of sanctions looks to begin anew. Economic sanctions have long been the preferred tool for the US government for a variety of reasons stretching back to the Cold War, where the US imposed economic sanctions against a variety of Communist-leaning countries around the world. The track result however, as scholars like Robert A. Pape point out, has been mixed at best. Sanctions against Latin American countries failed to directly be responsible for desired changes and appear to have more often than not led to greater instability in such countries. Cuba, where longstanding US sanctions have only began to thaw is perhaps the best example of a country where US sanctions failed to work despite drastically affecting the country’s economy. This latter point brings up one of the fundamental challenges of sanctions, the enforcement and participation of all parties. In the case of Cuba, a Communist sphere was there to support it for an extended period and more recently nearby politically aligned states. The end of sanctions against Cuba is near, and rather than coinciding with the end of the Castro regime the sanctions ending coincides with an America that no longer sees the point of such sanctions; in essence, Cuba simply outlasted the US’ stomach for their enforcement.

Another criticism of sanctions is their ability to be twisted by leaders in the state targeted by sanctions. A present example is Russia where despite a drastically worsening economy US-led sanctions have failed to achieve their aims. Surprisingly, despite the deteriorating economic situation large swaths of the Russian people, especially the younger generation, feels more optimistic about their lot post-sanction implementation. Russian President Vladimir Putin has deftly controlled the domestic discussion around the sanctions and the Russian economy to frame it in nationalistic tones of the West once again trying to undermine Russia. The imposition of sanctions, rather than bringing presssure to bear on the Russian government has actually played into their larger narrative of Russia vs. The West. Whether this narrative will ring true in the coming months remains to be seen. However, it is important to note than Central and Eastern European states, most notably Hungary, have been less than enthusiastic about the enforcement of the sanctions due to their relative economic dependence on Russia. It is worth noting that there is little evidence that the sanctions themselves are responsible for the economic situation in Russia as larger economic factors including the falling price of oil and a struggling Chinese economy likely having a more significant impact on the Russian economy than any sort of “targeted” sanctions.

What of the case of Iran, where a landmark agreement has been achieved with credit largely given to the promise of lifting Western economic sanctions against the country? Commentators have argued that perhaps the real reason for a thawing of relations between the West and Iran is the need for the US to re-incorporate Iran as a responsible stakeholder in an increasingly unstable region. Iran has long been suspected of being able to exert a large amount of power in Iraq that could be extremely beneficial against the continuing problem that is ISIS. Were the lifting of sanctions then less a sign of Iran capitulating and coming to the table, or a change in the US’ calculus on Iran’s ability to help with its more immediate goals? The evidence seem so support the latter.

Sanctions are extremely good however, at allowing political elites in the country applying the sanction to appear to be “doing something” to combat a problem that has sparked the energies of a particularly strong interest group. In times of elections, tough rhetoric around sanctions has been linked to a boost in the incumbent’s political standing as they can appear to be the “strong, decisive” leader. Sanctions are also shown to be effective at placing a greater burden on the average citizens of countries targeted by sanctions. Various scholars, most notable Mark R. Amstutz in his examination of “just war” in International Ethics, have effectively argued against the use of economic sanctions on these moral grounds. North Korea is a classic example of a country where despite overwhelming economic sanctions the political elites have been able to live a life of relative luxury despite large swaths of people dying of starvation. Those who have politically staked their reputation on helping the starving population despite the chance that such support would be diverted to the coffers of the North Korean elite have been resoundingly criticized by the their constituents. Kim Dae-Jung’s Sunshine Policy in South Korea is a classic example of a morally just program being criticized for appearing soft against the adversary.

The use of economic sanctions also has a dubious track record in the selection of countries they are issued against. In contrast to the comparably liberal Iran, the fact that Saudi Arabia practices barbaric sentences, including stoning, violence against homosexuals and forms of indentured servitude towards foreign workers and has not been targeted by sanctions illustrates the moral bankruptcy of the Western powers who are most likely to impose economic sanctions. The reason for this should be clear due to the very economic nature of the sanctions. Simply, if you are a state with enough economic clout to be valuable to the larger international economic order, you can be assured that you will be free to pursue whatever internal policies you please without fear of censure.

It is perhaps a comforting thing to consider that in the modern age the trend to resort to violence to settle international disputes has largely been replaced by the use of economic sanctions. It may be proof that, as some have argued, we are living in the most peaceful time in human history. However, the use of economic sanctions to settle disputes is still rife with moral ambiguity and an inefficient track record. Indeed, in settling international disputes perhaps it is time to go back to the drawing board.

Leggo My Ego; America’s Struggle With Police Brutality

https://youtu.be/udZF3b3oluY

On Thursday Afternoon, July 16th, Sheriff R. Glenn Smith received a copy of a Special Inspection Report from the Texas Commission on Jail Standards. It was determined that deficiencies exist. They were as follows:

Item 1: “Country officials were unable to provide written documentation to prove that all jail staff underwent two (2) hours of training on a yearly basis by the local mental health authority for that region in accordance with their approved Mental Disabilities/Suicide Prevention Plan on file with TCJS. This training is to include the recognition, supervision, documentation and handling of inmates who are mentally disable and/or potentially suicidal.”

Item 2: “Documentation received and reviewed by the Commission revealed that Waller County is not completed visual face to face observation of all inmates at least once every 60 minutes as required by Minimum Jail Standards.”

The approximate 8:00AM contact with inmate Sandra Bland was on the intercom system and not in person, as required. While both jailers have received mental health training it has not been done in the past year by the local health authority as stated in our own policy.

At this time we have no reason to believe that either of these deficiencies had any part in the death of Ms. Bland. However, Sheriff R. Glenn Smith will not tolerate disregarding policies and/or rules of the Texas Commission on Jail Standards, along with our own. As previously stated, we will be working on any improvements that can be made to see that this type of tragic incident never happens again. This will include personnel changes if needed. Specific details of Ms. Bland’s booking information cannot be released at this time [sic].

Trooper Encinia has since been placed on administrative leave for violating what the Texas Department of Public Safety calls “the department’s procedures regarding traffic stops and the department’s courtesy policy.” Not to mention this pesky thing called the Constitution.

The Texas Department of Public Safety announced an investigation into Bland’s death in conjunction with the FBI and the Texas Rangers. The District Attorney has announced he intends to convene a grand jury once the investigation is complete.

Title 5, Chapter 19, Section 19.01 of the Texas Penal Code states that “A person commits criminal homicide if he intentionally, knowingly, recklessly, or with criminal negligence causes the death of an individual.” Criminal homicide is described as “murder, capital murder, manslaughter, or criminally negligent homicide.” Section 19.05 defines criminally negligent homicide as an offense causing the death of a person by criminal negligence.

Failing to signal a lane change is not punishable by arrest. Bland’s death is a categorical result of trumped-up charges of assault on a police officer. She was in her car; how could she possibly have assaulted Trooper Encinia? As we can see from the dashcam of Encinia’s cruiser, she did not. First, he claims she is under arrest for resisting arrest and then once she is detained, she is charged with assault on a police officer? This defies all logic and doesn’t make any sense at all. It almost seems like Encinia was just winging it and making things up as he went along. Sandra Bland was unlawfully detained and illegally arrested by Trooper Encinia. That Encinia was suspended is a prima facie admission by the Texas Department of Public Safety of his negligent actions throughout the entirety of the traffic stop. This is the textbook definition of Texas Penal Code Title 5, Chapter 19, Section 19.05. Encinia was derelict in his duties which directly resulted in the death of Sandra Bland.

It would not be unprecedented for the District Attorney to bring charges against Trooper Encinia. As mentioned above, six Baltimore police officers have been indicted on charges ranging from depraved-heart murder to manslaughter to second-degree assault regarding the death of Freddy Gray. All were indicted for reckless endangerment and misconduct in office, as well. Confidence in police is at its lowest point since the Rodney King trials in 1993. This is not indicative of a venerable democracy that the United States is expected to be.

The purpose of this post is not to bash police or incite anti-police sentiment. Police officers lay their lives on the line to protect the communities they serve and dozens die in the line of duty each year. The work they do is inherently dangerous. This does not, however, grant them cart blanche to ride head-and-shoulders above the law. We can revere the work of law-enforcement officials while at the same time holding them to higher standards. These are not and must not be mutually exclusive concepts. In this case, however, the evidence is clear; Sandra Bland deserves justice.

The above is a republication from Human First, a human-rights-themed blog focusing on human rights issues across the globe.