One Step Forward, No Steps Back: Changing the U.S.-Iranian Relationship

On July 14, 2015, after endless hours of tense negotiations, the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCAP) was unveiled to the world. In the United States, it was hailed as a victory for the non-proliferation regime while others expressed frustration at the number of capitulations the U.S. had made. But the more optimistic supporters of the deal celebrated the rapprochement and suggested a possibility for closer American-Iranian ties. Unfortunately, mere days after the conclusion of the agreement, Grand Ayatollah Sayyid Khomeini, Supreme Leader of Iran, squashed any hopes of more cooperation.

Sumitha Kutty, an Associate Research Fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore, offers a very cogent analysis of the prospects of improved relations here. Put simply, the outlook for true détente is grim.

The U.S.-Iranian relationship is scarred by two major events. The first is the 1953 coup d’état engineered by the CIA and the British SIS. In response to the nationalization of the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, the U.S. deposed and replaced the popularly elected Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh with the pro-Western monarch, Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi. The second event was the Iran-Iraq War (1980-1988). During this long and bloody conflict, the United States supported Iraq through armament, training, intelligence, and most notably, the sale of chemical and biological weapons. Not only did the U.S. stay mum on Saddam’s liberal use of chemical weapons, it blocked a number of the United Nations’ resolutions condemning Iraq for the use of WMDs. Publicly, Iran cannot so easily abandon its enmity with America. It has spent the last three decades building political legitimacy around demonizing the United States. The U.S. State Department, on the other hand, lists Iran as one of the most active state-sponsors of terrorism with alleged ties to Hamas, Hezbollah, and al-Qaeda.

The United States, however, should look past the bitter rivalry and try to create a new pattern of cooperation. Negotiators should be debriefed and try to identify and cultivate more meaningful relationships that may have formed with their Iranian counterparts. The two powers share a fair number of overlapping interests. Sectarian violence, the Islamic State, Iraq/Syria, and Afghanistan are the most obvious. While none of this sounds very feasible, there exists a historical precedence.

After the attacks on September 11, 2001, Iran joined the rest of the world in offering condolences and sympathy to the United States. It surprisingly softened its rhetoric, briefly ceasing the familiar cries of “Death to America” that were a regular feature of public gatherings and addresses by clerics and officials. But it turned out to be little more than a moment’s respite. On October 7, 2001, cruise missiles and bombers began to fly through Afghani skies in retaliation for 9/11. Iran immediately began to publicly condemn the airstrikes and attacks. But things were different this time around.

Amidst all the condemning and denouncing, there was a fair amount of behind-the-scenes cooperation, many of which were initiated by Iran. Iran opened up the northeast city of Mashhad, in the Khorasan Province, for American aid to reach Afghan refugees. Additionally, Iranian officials sent secret messages to Washington expressing their willingness to perform search-and-rescue missions for U.S. pilots that may crash, be shot down, or force-land in Iranian territory. Then-Secretary of State Colin Powell, expressing surprise at the offer, remarked, “I don’t think that will be necessary because I can’t envision us needing it in that part of the theater. But it was an interesting statement on their part.” And there were an increased number of U.S. visits by Iranian senior ministers to meet members of Congress, former officials, academics, and business executives. Unfortunately, progress was completely halted by President George W. Bush’s infamous “Axis of Evil” State of the Union Address in 2002.

Returning to the old pattern of U.S.-Iran antagonism is not advisable. Thirty years of neglect and rivalry has brought the United States nothing but a fierce and relentless enemy and an enduring obstacle against the U.S.’ Middle East Policy. Prospects of an alliance or a special relationship, à la United Kingdom or Japan, are out of the question, but limited cooperation and increased interaction is certainly possible and can bring the U.S. some tangible benefits. Through repeated interaction, the United States can help mold Iran’s behavior as it gradually rejoins the world. This is not an attempt at complete social reengineering, nor is it a way to infringe upon Iranian sovereignty. It is a way to reduce the chances of Iran acting against American interests. There needs to be serious and effective diplomacy to encourage Iran to use its new influx of wealth to become a responsible stakeholder in the existing regional and world order. Isolating Iran again will only encourage it to seek refuge in the arms of U.S. rivals, like Russia or China.

The partnership should begin by focusing on the most pressing regional issues. The most obvious points of cooperation are the Islamic State and rebuilding Afghanistan. If the negotiations surrounding the nuclear deal are any indication, future cooperation between Iran and the United States will be grueling and frustrating. But this is not a justified excuse to revert back to old habits. Going back to the old ways will make Iran a problem rather than a potential solution. Yes, the deal is not perfect, but it is the best we have. It can provide a springboard for a more productive future. As unsavory as the two countries find each other, there have been stranger bedfellows.

The Precariat – When Insecurity Dominates

Only one in four people in the work force worldwide have a secure job with a permanent contract. The remaining three-quarters are employed “on temporary or short-term contracts, working informally without contract, self-employed, or in unpaid family jobs,” according to the International Labour Organisation (ILO). As a graduate student, finding this out has done nothing to allay fears of becoming gainfully employed after graduating, although quite frankly, and perhaps more depressingly, the findings are not exactly surprising. The post-crisis era has seen a marginal recovery in some economies, but job creation is slow and the actual jobs being created are only designed for part-time employment.

Temporary jobs, albeit inherently insecure, are not all bad; they are the first jobs people go into after graduating to get a foothold in their desired career. There used to be the expectation of guaranteed progress towards a more permanent position. These expectations are now laughable. The financial crisis has forced people who were laid off from these permanent positions to pick up whatever odd jobs they could find to support themselves—a step down from which it is still hard to recover from even now. This lack of security, combined with the lack of a safety net and professional identity builds frustration and contempt among those who feel they cannot construct an identity whereby they can pursue both work and play in a narrative they want to create.

This group of troubled people has been labeled differently in each country, from Japan’s “Freeters” to the U.K’s “Not in Education, Employment or Training (NEETS).” The label that seems to be gaining more traction in recent years, however, highlights the actual sentiment felt by these groups: the precariats. Economist, Guy Standing, has popularized the term, defining the precariats as a “class” of a “rapidly growing number of people facing lives of insecurity, moving in and out of jobs that give little meaning to their lives,” among other things. Consisting of the unemployed, migrants, and students in tertiary education, this class is by no means homogenous; women outflank men in demographic composition.

The birth of this class can be traced back to the 1970s when neoliberalism strode hand-in-hand with globalization to replace the ailing welfare states, paving the way for the market mechanism to make decisions for the economy. Standing remarks on an increase in “investment, employment, and income flow to where conditions are most welcoming” since then has been further exacerbated by the fact that 2 billion more people now live on the planet. By effectively replacing stable jobs with offshoring, casual labor, and peripheral and informal economies, on top of re-regulating the market so that companies can write the terms and conditions of how their employees can benefit from state policy, the system was re-wired to keep companies cost-effective and to prevent labor from putting up barriers like unions to reduce their competitiveness.

It is not unusual to see immigrants and the unemployed in this class—arguably the most alienated groups in society—as they are often treated with little sympathy by the masses. What is perhaps more peculiar is the inclusion of highly educated students in the precariat. Even students who are highly educated and looking for work after graduation are having difficulty achieving full-time employment. While it is of course expected that graduates do not find permanent work initially, two factors can be observed as contributing to this phenomenon over the past decade that has made the search for permanence and security a worryingly indefinite one.

Firstly, (and I think this is no surprise,) is debt incurred, ironically enough by trying to obtain an education to propel oneself into a desired occupation. In countries where student loans are not interest-free, paying them off while working part-time with no certainty of whether one can keep one’s job (let alone move up the ranks) is stressful, and the job itself is often unfulfilling and irrelevant to the desired career path.

This dovetails quite nicely into the second factor, which is probationary employment: apprenticeships and internships alike. These positions are supposed to help secure employment later on, but are now used instead as the company’s means of acquiring cheap labor, pitting hopefuls against each other for work that does not even guarantee them job security after. On a larger scale this reduces wages and opportunities that are already few and far between, preventing graduates from getting work at all, much less work that pays them poorly.

Students along with other members of the precariat class face growing frustration and anxiety over the little security they have while the rich luxuriate in it. This can produce dangerous results if the imbalance remains unaddressed. The chronically insecure are observed to develop lower tolerance and altruism, allocating the blame of their societal position to outsiders—immigrants, who are funnily enough also part of the precariat. Additionally, because these insecurities have forced people to focus on short-term day-to-day survival, they are also less likely to be politically engaged. Fewer people belonging or voting for their parties out of apathy or disillusionment has also yielded a general drift to the right. This leaves little time and remaining energy to think more seriously about the long term, and to properly participate in civil society that could aid in alleviating their problems.

So, what is to be done? And what can be done? Although these are questions that cannot be fully answered, several economists (including Standing) cite a universal, unconditional basic income and a deliberative democracy as the fundamental requirements for providing the precariat with security and a feeling of inclusion in a society they are alienated from. By adopting elements of consensus decision-making as a product of fair discussion and reasonable debate among citizens, they become more engaged in the state’s democratic process. These two proposals are by no means without flaws, but the fact remains that insecurity among a large section of the global population must be addressed if we are to reduce the possibility of unrest and budding political extremism.

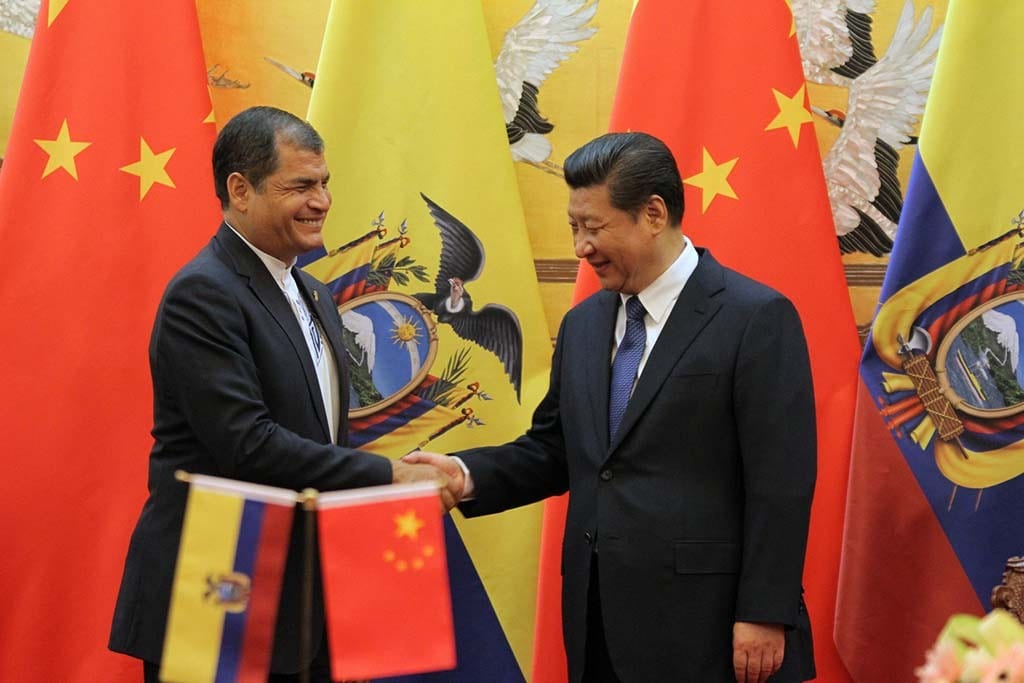

China in Latin America: Sister Country or Neo-Colonialist?

Ever since the end of the 15th century, Latin America has been seen by outsiders overwhelmingly as a place rich in natural resources. In the 21st century, the most recent outsider, China, is as hungry for its raw materials as any other previous power. It needs Argentinian agricultural products for its fisheries and pig farms to feed its growing middle class. It needs Bolivian and Peruvian iron and copper to continue building its manufacturing industries, and Ecuadorian and Venezuelan oil to fuel them. Past encounters with foreign powers in Latin America reveal a patter of resource extraction and economic dependency that benefited primarily the outside power and the local elite. Some, most notably Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro, in the region say that relations with China will be different, that China is a partner and a sister country, not an imperialist outside power. These optimists are hoping for a reinvention of the relationship between resource hungry outside powers and natural resource rich nations in the region. Unfortunately, Chinese recent forays into the region appear to be mirroring this tragic historical pattern.

Israel’s Other Human Rights Catastrophe: The Negev Bedouin

The plight of the Negev Bedouin continued as Israel’s Supreme Court recently ruled that the village of Umm al-Hiran would be destroyed and its inhabitants removed to make way for Israeli settlers. The NGO Human Rights Watch criticized the ruling, which also applied to a similar village in the West Bank, with its Middle East and Africa director Sarah Leah Whitson stating “The court decisions in the Umm al-Hiran and Susya cases ignore international law in upholding discriminatory evictions by the Israeli authorities in Israel and the occupied territories”. (more…)

The Business of Death

The Chinese life insurance market has grown exponentially since the start of the millennium. Now the fifth largest life insurance market globally, sales have risen from 98 billion yuan in 2000 to 994 billion yuan in the first half of 2014. What perhaps makes this feat more impressive is not only the speed at which the market has expanded, but also the success of being able to market such a product in a culture where discussing death used to be completely taboo. To understand what exactly happened here, we need to rewind the clock a bit, and add a little contextual color.

Just as the phrase “to have a good life” can mean multiple things, “a good death” is equally as ambiguous. In the west, Christian cultures in particular view death as a promise (or threat) of an afterlife, depending on how you act during your earth-bound existence. In China, where Confucian values are heavily embedded into culture, the subject of death is rarely discussed mainly due to its ambiguity, and it is almost always negatively portrayed. As if mystifying it wasn’t enough, Taoist beliefs measure how good a death is based on its timing and nature—anything other than dying of old age and with descendants was deemed terrifying due to the threat of spirits angry at an unfulfilled life.

For life insurance companies, this creates a bit of a challenge. What can they do to sway the public to buy a product that is synonymous with sacrilege? How dare a company put a price on something as sacred as a life, let alone one that has ended prematurely! In Victorian England, they overcame this obstacle by exploring (and exploiting) the impact of the death of a breadwinner on his family, marketing their product as a form of family responsibility, where the deceased can remain productive for his family even after death. The family ethos in China also makes insurance marketable in this sense, although this alone does not attribute to the market’s growth.

Mentioning terms like dividends, customers were more likely to buy insurance as a form of return on one’s purchase that could be put down as savings for your child’s future or your parents’ care. Like in many Confucian cultures, saving for the future plays a prominent role in spending (or rather saving) habits, and with the average urban household savings rate at 25%, it is not surprising that a product that seems to make savings easier became so popular. It has also become a popular gift to give to your children and your friends, in keeping with the tradition of renqing (人情), the act of giving another person a gift or resource as a gesture of goodwill, especially on special occasions.

The wealth accumulating in China has created an affluent middle class with more disposable income. With this wealth more people are moving to the cities, leading to urbanization rates increasing from 47% in 2010 to a predicted 59% by 2020, equating to around 200 million more urban people. With closer access to life insurance, it is quite likely that these new urbanites will purchase life insurance, given cultural habits of saving as well as plenty of policy options to match their needs.

Since the 1990s, life insurance in China has gone through its peaks and troughs, mainly being able to overcome the slack in market performance with growth drivers. High-yield products guaranteeing returns of almost 10% in the late 1990s, universal and participating products, which consisted of dividends and tax-advantaged policy options respectively, boosted the market up until 2005. When the bancassurance model (bank and insurance company working together to sell policies) was introduced into the market along with high returns, insurers were given the extra push to reach the top ten in the world based on their performance.

Since 2011, however, there has been a slow-down in policy purchases, with bancassurance model setbacks and no growth-drivers sufficient enough to turn the market around. The 30-40% growth rates enjoyed in the early ‘noughties’ are probably not going to be repeated without a huge overhaul in current regulations. Unlike the U.S., the government in China provides little tax incentives for people purchasing premium insurance policies, with only 10% of the premiums being tax deductible. More widely available deductions could be the sufficient condition to drive growth in the life insurance market in the future.

However this plays out, the life insurance market in China is just one of the many examples the country has produced of markets expanding at unprecedented rates as a result of changing mindsets and demographics. The sheer size of the market magnifies any changes in regulation as well as the lack thereof. Unless life insurance finds its new driving force for growth, it may find itself unable to revive, and other non-life insurance companies competing for sales will step up to the plate of providing an attractive service to its customers.

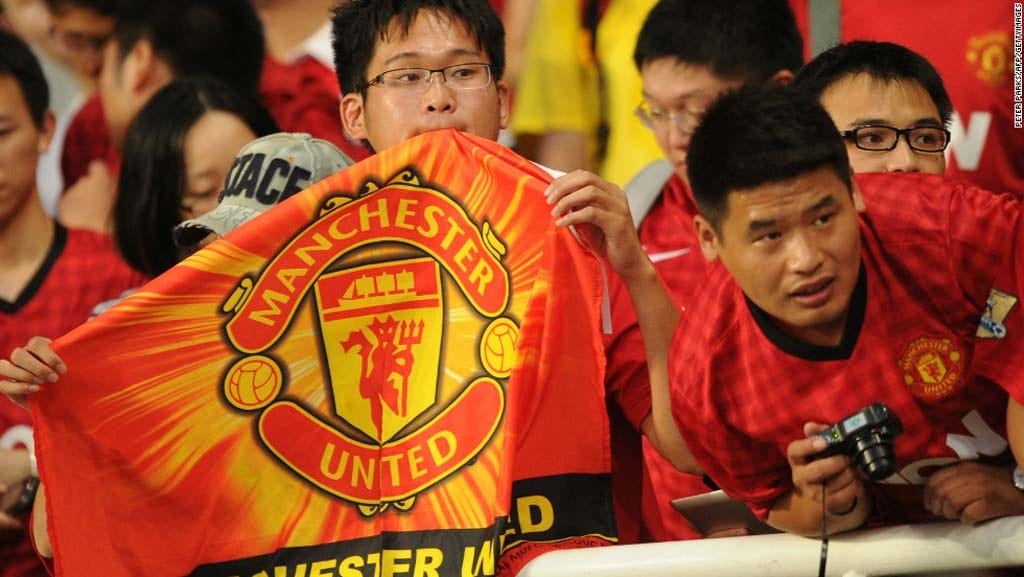

Bringing Football to Asia

Chinese president Xi Jinping has set his country’s national football team three targets to aim for: qualify for the FIFA World Cup, host it, and win it. Football has even been made compulsory in national schools, and projects for the construction of sports grounds have been passed swiftly to ensure the country can achieve its hat trick. As amusing as it may sound, Xi is by no means in the minority when he expresses his obsession and hopes for the sport. The hype over football has reached new heights, especially since the commercial success of January’s Asian Cup, a strong indicator of the game’s popularity across the continent of 4 billion.

When the national teams aren’t playing however, the majority of attention is given to overseas European football rather than local teams. Worldwide interest has skyrocketed over the past decade and a half due to weekly coverage in mass media and on social networking sites like Twitter and Facebook, connecting fans on both national and international levels to these teams. But why is European football especially popular in Asia?

For the English Premier League alone there are an estimated 820 million supporters in Asia, according to sports research company Repucom. Manchester United claims that they have 100 million fans—and that’s just in China. Manchester City, too, has been gaining ground in recent years, with five times as many fans in Asia (16%) as there are in the U.K. (3%). This commercial success in Asia can be explained by the region’s unparalleled growth, where increasing amounts of disposable income for the growing middle class has seen greater spending on cable subscriptions and merchandise. An absence of any equivalent to major European Leagues in Asia has also made it easy for big clubs to enter Asia without much local competition.

The commercialization of the European leagues has also been triggered by the introduction of Financial Fair Play (FFP) rules, a response to clubs who were encouraged to borrow money to obtain better players and more points in their leagues, even if it meant they couldn’t break even. The Union of European Football Associations (UEFA) introduced FFP to reduce incentives to make losses, punishing clubs exceeding spending over several seasons—the most severe consequence of breaking these rules would be disqualification from European competitions. Such restrictions have motivated teams to work on their club brand overseas. With the potential for huge fan bases in Asia, it is unsurprising they are spending their summers touring Asia in friendly matches and competitions with local and even other European teams.

In Korea’s own K-League, for instance an average of 15,000 people usually attend matches. But when German team Bayer Leverkusen came for a friendly last year, the number of attendees tripled, filling the stadium—mainly due to the inclusion of “the future of Korean soccer” duo Son Heung Min and Ryo Seung Woo. It seems the patriotic streak in countries that have their nationals playing in Europe shows colorfully during these tours. Something similar happened when Manchester United toured around Asia back in 2012, where shirt sales for the only Asian on their first team, Japanese attacking midfielder Kagawa Shinji, surpassed $300 million.

What seems to be happening here is that with all the financial attention given to the big leagues, little is left for the local ones. When football can be enjoyed in the comfort of one’s home, a new angle needs to be found to win the hearts of local fans. Some sort of brain drain has also been observed with talented footballers leaving for Europe when given the opportunity, making the development of Asian leagues less sustainable. Japan’s J-League has defied this somewhat with its local competition becoming stronger even with its best players moving to Europe.

Could China reverse this trend? Its teams are being coached by old timers in Europe, and have some of the most well-paid players in the world too. On top of this, they have the opportunity to grow without the restrictions UEFA have put on European leagues. China’s own Super League has had to overcome other obstacles in recent years due to the increase in attention and investment it’s receiving from Chinese companies; match-fixing and illegal betting are rampant in the league still, and even though the government is starting to take steps to fix this (the top executives of the Football Association of China were prosecuted in 2012 for taking bribes), it remains a problem to this day.

China could very well win a World Cup before England does, (although after half a century of not winning I would argue that there really isn’t that much of an achievement in that respect,) but how it, as well as other countries in the region will reach global recognition, is a journey I, at least, am very interested in seeing the development of.

Decentralization Process in Peru

Ideally the modern state is supposed to generate the necessary basic conditions for its citizen’s wellbeing and continuously improve its own systems in order to improve its citizen’s quality of living. The globally trending prescription to achieve these aims is decentralization and local governance. Several countries, such as Korea, Brazil, Thailand, Uganda, Indonesia, and Peru, among others, have all recently tried to strengthen local governments.

In larger countries and countries with diverse populations, such as Peru, it is especially necessary to disseminate the central government’s power and authority to local and regional governments. In that way, each sub-government can communicate with citizens directly and can serve them faster and more efficiently. According to The Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), Peru has developed its GDP 5.2% in the past 10 years. In addition, the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) Human Development Index (HDI) shows an increased HDI rate from 0.67 in 2002 to 0.73 in 2012. However, the problem that Peru faces is that the development of the country did not happen evenly in each region, but is rather predominantly concentrated in Lima, the capital of the country and the location of the central government. It would not be unsurprising if visitors to Lima alone came away with the impression that Peru is a well-developed country. However, the country faces extremely large gaps between rural and urban areas regarding basic necessities such as public infrastructure services and in economic measures such as the poverty rate.

The Peruvian government officially began to enact a decentralization process starting in 2002, but as of yet the plan has yielded little meaningful results. Moreover, some academics and politicians blame inefficient and abstract planning as contributing to the prevalence of corruption at the regional government level in the last few years. The root of the problems with Peru’s decentralization process is that the plan was elaborated macro-regionally, without attention to finer details in execution and with no concrete political division. Thus, the government could not provide appropriate training in management, accountability, and transparency for public administrators and governors. Peru held a regional presidential election in October 2014, and despite this is still experiencing a persistent problem of corruption such as money washing, bribing, hiding money, and so on. After the new regional presidential election, the National Assembly of Regional Governments also designated the president from one of the regions in Peru, La Libertad, as the organizational president to represent at Congress in January 2015. After he was elected, he promised that he would try to promote the creation of a regional community of project management for local development and will unite efforts and resources. This mancommunidad envisioned sharing financial resources and “best practices” to better strengthen regional governments. However, since then no noticeable action has been taken, nor have agreements been made in the absence of effective training for leaders and the long-term period of corruption.

Generally the decentralization process is most successful when it coincides with financial decentralization, but this cannot be considered yet in the case of Peru where political decentralization problems have not been fixed and no effective political division planning has been carried out. In order to support the Peruvian decentralization process, international organizations, NGOs and international cooperation agencies must execute projects and programs along with the National Decentralization Council under the leadership of the President of the Council of Ministers. So far the Peruvian government and the organizations involved have followed Act 27783 Bases of the Decentralization, which defines the norms that regulate the administrative, economic, productive, financial, tax and fiscal decentralization to national, regional and local governments. While this is a welcome step, Peru would benefit from the government’s further embrace of the Act’s aims. Finally, a new presidential election is coming up in 2016, which presents a fresh opportunity for the country. This is the time for the Peruvian government to take strong action in facilitating the transition to a new administration that completely and effectively embraces a decentralization process.

Blaming Europe and Arresting Smugglers Will Not Solve the Mediterranean Migrant-Crisis

The United Nations estimates 60,000 people have tried to cross the Mediterranean this year. Nearly 2,000 have died this year trying to reach Europe from Africa. This is a 20-fold increase for the same time period in 2014 where fewer than 100 perished at sea. 800 of these deaths occurred in the middle of April off the coast of Libya when a fishing trawler collided with a Portuguese container ship. The current lack of law and order in Libya has led to a situation where no state entity is able to control territory, borders – and or sea. As such, hordes of smuggling gangs have manifested and acted with impunity.

Migrants hoping to reach Europe are often told they are purchasing a seat on a “big boat.” More often than not, however, what is waiting is a small dinghy where they are forced to enter at gunpoint. Those who refuse are reported to be shot. Before boarding, migrants are held prisoners on a farm for weeks and sometimes even months before departure where reports have emerged of abuse, beatings, sickness, starvation, and death.

Survivors of the accident mentioned above claim the smugglers wanted to fit 1,200 people on the 66-foot boat. Those on the doomed fishing trawler mentioned above paid between $700 and $7,000 to board. Passengers with the least amount of money were stuffed in the hold.

Not all rescued migrants share the same fate. Those picked up by the Libyan coast guard are held in detention until their country of origin is determined and are then deported. Migrants picked up by European rescuers have somewhat more fortunate circumstances. Upon reaching ports in southern Europe such as Catania in Sicily they have their names and photographs taken by authorities and are then moved to Red Cross tents where they receive food and shelter.

Lawrence Jolles, a spokesman for the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, says that at the moment, the UNHCR has less-than-adequate capacities for rescuing these migrants who choose to flee their country of origin for Europe. Leaders from the European Union have pledged to triple funding for Frontex, the EU border agency, and have even gone so far as to threaten military strikes against smugglers’ boats. While the UNHCR says the EU needs further mechanisms other than its current spending plan, this is an improvement over the former plan of cutting the number of rescue boats in hopes of discouraging migrants from crossing the Mediterranean.

As weather improves, more migrants will make the journey. The question therefore seems to be how to stop people from risking their lives trying to reach Europe by means of human smugglers. Some have suggested joint UN-EU safe zones be set up in North African countries where migrants can apply for asylum before embarking on the treacherous journey. While noble, this is an unlikely solution. For starters, Libya currently has two rival governments operating within its borders. Secondly, most migrants fear they are not eligible for asylum and would be labeled as economic migrants (as absurd as that may be). Europe in general and Britain in particular has received a lot of flack for its perceived failure to act. As Stefan Soesanto of the Pacific Forum Center for Strategic and International Studies notes, it is easy to blame Europe, yet the reality of the situation hovers between “an open-door policy that allows for overall legal migration to Europe and… a full-fledged deterrence policy that militarizes European maritime security and border surveillance.” The EU has put together a ten-point plan to combat the crisis that is a hybrid of the two. The plan, backed by foreign and interior ministers, is as follows:

1. The EU will reinforce the EU’s maritime patrolling operations in the Mediterranean, called Triton and Poseidon, by giving them more money and equipment. The EU will also extend their scope to patrol a wider area of sea.

2. The bloc will make a systematic effort to capture and destroy vessels used by the people smugglers, using the EU’s counter-piracy “Atalanta” operation off Somalia as a model. EU officials said it would be a combined civilian and military operation but gave no more details.

3. The EU’s law enforcement, border control, asylum and prosecutors’ agencies will meet regularly and work closely to gather information on how the smugglers operate, to trace their funds and help investigate them.

4. The European Union’s asylum support office will to deploy teams in Italy and Greece for joint processing of asylum applications.

5. EU governments will fingerprint all migrants.

6. The EU will consider options for an “emergency relocation mechanism” for migrants.

7. The European Commission will launch a voluntary pilot project on resettling [5,000] refugees across the EU.

8. The EU will establish a new return program for rapid return of “irregular” migrants coordinated by EU agency Frontex from the EU’s Mediterranean countries.

9. The EU will engage with countries surrounding Libya through a joint effort between the Commission and the EU’s diplomatic service.

10. The EU will deploy immigration liaison officers abroad to gather intelligence on migratory flows and strengthen the role of the EU delegations.

This is a step in the right direction, however as the BBC’s Chris Morris notes, the current funding for rescue operations is at 1/3 of what it was last year. Doubling that funding, which is what the EU has proposed, will still be less than the amount of funding received in 2014. Also, the pilot program designed to admit 5,000 asylum seekers sounds good, but this number is a drop in the bucket compared to the 170,000 refugees admitted in 2014 in Italy alone. Furthermore, going after smugglers is a monumental task. Will the EU authorities go after boats? If so, will this be through targeted military operations or by destroying abandoned boats at sea? As Patrick Kingsley of the Guardian explains, smuggling operations include more than just the boat drivers. There are brokers, drivers, people selling wholesale life jackets, boat owners, passport forgers, and bribes for the coast guard to look the other way. Even if all the smuggling networks are taken out, the demand to reach Europe will still be present. Blaming Europe or blaming the smugglers is not what the global community’s voice should be targeting. If the ultimate goal is to prevent flight in the first place, then we need to look at the causes for flight.

The majority of migrants rescued at sea come from places like Nigeria, where Boko Haram seemingly kidnaps girls at will for trying to go to school; Gambia, where homosexuality is illegal and President Al Hadij Yahya Jamen threatened to slit the throats of all gay men in the country; Ghana, who has been plagued with an energy crisis for the past three years; Syria, which is in the midst of a four-year-long civil war and also a stronghold for ISIS; Libya, which has fallen into chaos after the fall of Gaddafi and is on the verge of becoming a failed state; Eritrea, “a harsh, brutal dictatorship” called the North Korea of Africa; Somalia, which has been largely lawless and without a functioning government since 1991 and is terrorized by Al Shabaab; Mali, which suffered a coup in 2012; Sierra Leone, ground zero of the Ebola outbreak last year which is still ravaging the country; and Senegal, with rampant unemployment that reached 48% in 2014.

Whether it be for equal access to education, reliable infrastructure, sexual freedom, better medical care, or peace, refugees are fleeing their countries of origin in search of a better life and the prospect of a grim death while packed to the brim in the bottom of a dinghy is not nearly enough to deter them from doing so. While the multi-pronged approach proposed by the EU is a proper reactionary tool, another tenor must be added to this mechanism in order to preemptively gut the problem at its source. I am not suggesting military interventions, but rather increased foreign aid, investment, cooperation and engagement from developing countries in order to bring these nations into the 21st century where the rights of all are respected.

The above is a republication from Human First, a human-rights-themed blog focusing on human rights issues across the globe.

ISILationism, Part 3: Eventual Endgame or Endless Games?

In case you missed it be sure to check out the first and second part of the series, ISILationism, Part 1 and ISILationism, Part 2!

A question that must be asked when confronting Fundamental Islam is: where and when have terrorism and insurgencies faltered, ultimately failed, and reached complete fallout? The answer, as should be known, is: nowhere and not yet!

Salafi Jihadism, under the guise of some newly emerged radical Islam, has been an overt force in the world since the beginning of our current millennium, with no tangible sign for the hopeful demise of its existence. Al-Qaida rose from obscurity after the September 11th terrorist attacks on New York City to a globally renown, expertly organized network promoting the destruction of the “far enemies” in order to universally advent Sharia Law. This organization, however, has diminished in power and overall capabilities through the relentless strategies and countermeasures conducted by the United States to successfully subvert Al-Qaida. With the conclusion of military operations in Iraq officially declared and executed in 2011, a lessening concern for Afghanistan has also increased among public policy and public opinion in America. Additionally, the multinational forces have grown battle-weary and the exhaustive, perpetual struggles with the Near East’s intolerance for democratic implementation bear no eventual reward. Both conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan have met a kind of standstill at the edge of maddening continuity, where the only true dissolution of war rests in the authority of executive decisions to simply enact them.

Within this pervading ambiguity arises the causality of anything and everything, where hypothetical expectation may, indeed, occur but through infinite avenues of approach never initially supposed. Al-Qaida relinquished its strong foothold in Afghanistan and pushed further East into Pakistan to avoid more casualties, but this was no safe-haven as Osama Bin Laden was eventually targeted and killed at his compound in Abbattabad. The waning power of Al-Qaida exerted a strain on the Taliban, which now fends for itself in Afghanistan at the expense of Al-Qaida’s withdrawal and overall lack of authority with global terrorism. Yet, out of all the satisfaction and glory of America’s triumph in annihilating the monarch of modern terrorism, the sheer pride and amazement of victory had blinded leaders of the free world from another agent of chaos born from the fire and ashes of the Syrian conflict.

The hubris of the United States in the Near East apparently has no stopping point, as aiding and abetting the Al Nusra Front, among other rogue insurgents in Syria, proves just how effortlessly misjudged compromises can backfire. Syrian President Bashar Al-Assad’s forces have wreaked more carnage upon the land than the Islamic State, massacring civilians and rebels by the day and thereby necessitating a retaliatory militia that has come to be known as the Islamic State. Insurrection by an opposing force to overthrow the regime was a call to action on the sidelines of American involvement, but favored, nonetheless, as a preferred course towards ousting Syria’s dictatorship for good. This, undoubtedly, has not come to fruition and a new wave of terror inextricably linked to the regime has overwhelmed Syria; simply put, President Bashar Al-Assad’s irreverent disregard for human rights and totalitarian onslaught has been, effectively, the “fuel for the fire” of insurgency, that burns evermore explosively with ISIL.

Rapid accession of the Islamic State from across the globe currently takes precedence as a universal matter to be reckoned with, but the intrepidness of foreign fighters uniting with ISIL is most striking–many have left a life of luxury to partake in a violent cause for the hardline implementation of Sharia Law! This phenomenon transpired with Al-Qaida and the Taliban fighters, a significant minority of whom where born in Europe and North America. But the appeal of the Islamic State is pulling in more and more warriors to level Syria and Iraq’s foundations. American foreign policy has now readjusted to cater to the Syrian regime’s initial focus, and the U.S. has taken the lead as a distant yet thoroughly involved observer. Regrettably, the forward momentum of such a switch in protocol has wide-reaching repercussions for America and such an immediate reversal perhaps gives the impression of desperation by the United States. This is unlikely the case though, and the more feasible reason is that ISIL is gaining worldwide support and the influx of new fighters may eventually bog the Syrian regime down to nil, where disorder and anarchy secede the country. If a true Caliphate by the Islamic State is to be founded it will be in Syria once Bashar Al-Assad has disappeared from the scene.

There are no “front-lines” and there never have been since the War on Terror’s inception; thus, by this condition, the finality of warfare can be as vaguely transparent as the covert operations themselves. The “War on Terrorism” itself is a rather obscure term defined by the curious juxtaposition of absolutism (war) and fundamentalism (terrorism). Such a conventional approach to unconventionality allows the latter to immortalize itself through elusiveness and zealotry, which would promote an ever-widening, ever-present danger at any time and any place. In other words, waging a war against an ideology so unassuming and invisible that it is virtually omniscient would be a campaign fraught with no ends! However, America and all those in opposition to Salafists must counter the threats of the Islamic State and global Jihadism in order to contain these crises, at best.

Anger Across the Water: Parallel Trading in Hong Kong

The conflict between Mainland Chinese and Hong Kong people doesn’t seem to have an end in any sense. After the influential pro-democracy demonstration in Hong Kong, another protest against Mainland Chinese traders buying up goods to make a profit back home took place recently, and is still going on at the time of writing.

Hundreds of Hong Kong residents have gathered to demonstrate against visitors from Mainland China. Hong Kong people are angry with these so-called “parallel traders,” who come to Hong Kong to stock up on lower-priced goods, including food items, luxury goods and electronics only to sell the goods for a profit across the border while dodging tariffs. The outrage has also spread to normal tourists, shoppers, cross-border buses and passersby with suitcases and trolleys from Mainland China. Social media has been awash with videos showing the activists attacking normal visitors from Mainland China, including old people and children, causing great rage and inciting another round of war online between Hong Kong people and Mainlanders.

Parallel trading in Hong Kong has a long history. The number of parallel traders from Mainland China grows each year and the problem has become even more serious since 2008, when tainted supplies of milk powder on the Mainland boosted demand for imported formula cheaply available and easily purchased in Hong Kong. Since then, there have been shortages of many kinds of goods in Hong Kong and it is no doubt that Hong Kong people’s daily lives have been disrupted due to the increase in prices of domestic goods as a result of not only parallel trading but enormous amounts of Mainland visitors.

While many Hong Kong activists have called for a cancellation of independent travel and same-day multi-entrance day visas, some Mainlanders have taken to social media to post pictures of cutting their “Pass to and from Hong Kong and Macao” certificates. These images have been posted and reposted along with a message saying “Support Hong Kong’s right to cancel free travel and give peace and tranquility back to Hong Kong people. But at the same time, support Guangdong in stopping supply of electricity to Hong Kong, and also stop the Dongshen water supply project.” This message pretty much shows the attitude and mindset of the Mainland Chinese towards Hong Kong people, accusing them of not being grateful for what China has been doing for Hong Kong.

This accusation is not true. The fact of the matter that Mainlanders may not know is the price Hong Kong pays for the water from Guangdong is extremely high and there is a minimum quantity per year Hong Kong is required to purchase. From 2012 to March 2014, Hong Kong paid around 2 billion HKD ($258,000,000) to buy water from Guangdong and the wasted water was all flushed into sea. Hong Kong media has compared Singapore’s situation with Hong Kong’s and estimated that the price of raw water bought from Guangdong is 10 times more expensive than the raw water Singapore buys from Malaysia. From 1979, Guangdong has been purchasing electricity from Hong Kong, meaning that the flow of electricity is mostly from Hong Kong to Guangdong.

Another truth is that most of the visitors from Mainland China don’t obey the rules in Hong Kong, such as eating in the metro, defecating publicly and so on. This kind of stereotype of Mainland visitors makes Hong Kong people think every Mainlander has no manners.

There is no doubt that the development of Hong Kong has a lot to do with Mainland China, but the situation is far from the perception that the Mainland is doing Hong Kong favors. The interaction between Hong Kong and Mainland China has become an economic and trade relationship after the Open and Reform policy and the return of Hong Kong in 1997. Many Mainland Chinese only see one side of the coin that Hong Kong benefits from the Mainland, but Mainland China also benefits a lot from Hong Kong. This free port has become an important example for China’s Open and Reform policy and has brought much foreign investment into the Mainland. Hong Kong has always been a bridge between Mainland China and the liberalized world.

Hong Kong people don’t consider both sides either. According to Hong Kong’s legislative council meeting, 94% of parallel traders are Hong Kong people. The numbers show that from September 2012 to February 2013, Hong Kong Customs uncovered 4,339 smuggling cases in all land border ports and arrested 4,325 people. 4,090 of the people who were arrested were from Hong Kong while only 231 Mainlanders were arrested. It is not fair to just criticize Mainlanders. It is also unfair to blame Mainlanders because the government legally allows them to enter Hong Kong multiple times a day. Why shouldn’t they consume better quality goods if they are able to?

The war online is rarely rational and the misinformation spreading through social media is making things much worse. Hong Kong and Mainland Chinese citizens have not reached any more of an understanding of each other now than they did at the handover in 1997. There are many Mainlanders who visit Hong Kong that are very polite and civilized, but it will never be on the news for Hong Kong people to see, so they may not know it. All the negative news and descriptions of Mainland Chinese in Hong Kong also solidify the stereotype of Mainland Chinese.

Conflicts between different regions happen almost everywhere in China, mostly between different provinces. Hong Kong is a special administrative region in China (S.A.R), but it is a city that has a governing system that the Mainland Chinese can hardly understand. Simultaneously, Hong Kong people can hardly understand the difficult situation of the Mainlanders. The emotion shown on the internet is too strong to allow people to think rationally, but the only way to improve the situation is to think rationally and have the all the facts.