Does Obama’s New AUMF Really Matter?

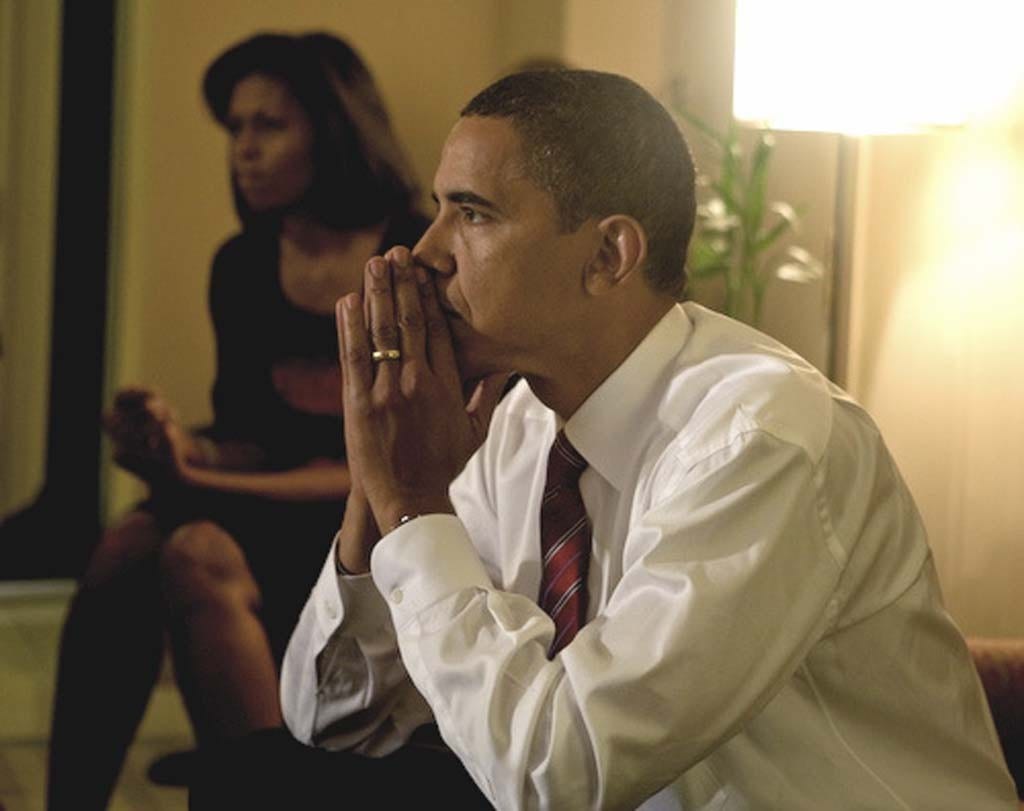

As reported on February 11th, US President Obama announced his plans to request the authorization to use force against the Islamic State (IS). In preparation for this, the White House released the proposed document, which it notes may be referred to as the “Authorization for Use of Military Force against the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant” (AUMF-ISIL). Although there has been signifiant fanfare and media coverage over the implications of the document, the proposal itself is not as game changing as reported. Largely, this has been a result of overeager media coverage concerning the document. Outlined in the three page draft are the administrations arguments as to why they are requesting authorization against the IS, in addition to limitations of the scope of action and on the executive branch’s powers. Most notable among these limitations pertains to Subsection (a) of the draft which formally requests authorization. In defining this subsection, the draft notes that it “…does not authorize the use of the United States Armed Forces in enduring offensive ground combat operations”. In essence, this prevents additional deployment of ground troops beyond those which already are present in what is defined as the scope of the theater. In addition, under Section 3 the duration of the authorization is limited to “…three years after the date of the enactment of this joint resolution, unless reauthorized”. Section 4 requires the President to report to Congress “at least once every six months on specific actions taken pursuant to this authorization”. The final and fifth limitation, and the one which is likely to generate controversy in the coming days, concerns itself with the exact definition of hostile actors to which the authorization pertains to. This section broadly defines these actors as “…individuals and organizations fighting for, on behalf of, or alongside ISIL or any closely-related successor entity in hostilities against the United States or its coalition partners”. In short, the preceding sections illustrate a document which appears modest and tempered in all but the definition of the US’ enemy.

Before critiquing the proposed authorization, it is important to understand the document from a legal point of view. Specifically, it is critical to understand what the document is and is not, and what previous authorizations or legal justifications it interacts with. A clear separation must be observed and understood between a AUMF and a Declaration of War. According to the US Government, an AUMF authorizes force “…against an either a named country or unnamed hostile nations in a given region” whereas a Declaration of War “…a state of war under international law and legitimates the killing of enemy combatants, the seizure of enemy property, and the apprehension of enemy aliens”. In addition, it is also critical to note that the latter also confers greater power to the executive branch to conduct operations whereas a AUMF does not. Given that the proposed draft is titled as a AUMF and includes explicit limitations on the executive branch, it is clear that both in essence and in spirit US President Obama does not foresee the need to request additional powers to combat the IS which would only be conferred through a Declaration of War. This interpretation, if correct, should help analysts and observers better understand the president’s thought processes. With regards to what the proposed AUMF replaces, it explicitly states that it is meant to replace the 2002 AUMF Against Iraq. Interestingly, and perhaps telling of the administrations calculations, it leaves the 2001 AUMF Against Al-Qaeda as active. This 2001 AUMF has long been used to justify actions against Al-Qaeda and Al-Qaeda affiliated groups regardless of their geographic location. In addition, the administration had relied on this document for the past year during its earlier actions against IS. This had caused many legal experts to argue that the use of force against IS has been illegal under US law, with Robert Chesney, a professor at the University of Texas School of Law, who referred to the use of the 2001 AUMF as justification for actions against the IS, stated “On its face this is an implausible argument because the 2001 AUMF requires a nexus to al Qaeda or associated forces of al Qaeda fighting the United States,” and that “Since ISIS broke up with al Qaeda it’s hard to make that argument.” Thus, this new AUMF would give the administration stronger domestic legal justification for conducting actions against the IS. In addition, the combination of the 2001 AUMF and the proposed AUMF together would allow the administration considerable freedom to both conduct combat operations against any number of “affiliated” groups and interpret the geographic scope of their mandate.

Internationally though, there remains several issues with which the Obama Administration will have to contend. The first is related to international law as laid out in the UN Charter which states “All Members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state.” Exceptions are allowed with Security Council authorization or in the case of self-defense. As none of these have been cited by the administration to justify actions against the IS, the Obama administration and the Bush administration have relied on other sources for interpretation and in justifying the use of force. Traditionally cited by these administrations is International Humanitarian Law (IHL), the law of armed conflict. However, the use of IHL by these administrations has been controversial. Specifically, there are several tests that must be passed for the framework of IHL to apply. These have generally been interpreted to apply a defined geographic scope to the conflict and requires a clear distinction to be made between combatants and non-combatants. In the case of combat action against the IS, which does not have a internationally accepted geographical territory and operates across various territories, the former test is not met. The recent US Administrations have not seemed concerned with attempting to meet this requirement either, as drone attacks have been conducted in a variety of countries. Second, the ability to distinguish which members of the IS are combatants and non-combatants is questionable at best in theory, and in practice has clearly failed given the high profile deaths of civilians by US forces.

The Obama administration’s proposed AUMF has generated considerable fanfare, and understandably so as the IS has proven to be an enduring scourge on the region and through its actions have horrified the world. However, the misconception surrounding its function and place in the greater scheme of US and international law must be observed. It is important to remember that this document is merely a proposal, which will most likely be heavily modified by the US House and Senate. In addition, while this AUMF tidies up the Obama Administration’s legal standing to conduct actions against IS from a domestic standpoint, it is not without its criticisms. As outlined before and covered elsewhere, the broad scope outlined in the limitations has been a call for concern. Internationally, the proposal does nothing to provide legal justification for US actions against the IS. This only highlights the continued failure of existing international legal regimes to properly operate in the realities of the present. While the administration should be applauded for its actions against the IS and its foresightedness to impose Congrssionally-subjected three year limitations on this AUMF, the administration would be well served in channeling the outrage at the IS’ actions into efforts to create a new body of international law.

What is the Future of the Assembly Line?

Production changed drastically during the last century and is continuing doing so without loosing any momentum. The most recognized technological shift occurred with Henry Ford’s use of the assembly line and progress has continued in a variety of fashions. One of these that is often overlooked is the use of robotization, an example being KUKA robots, which have reinvigorated factories over the past decades. Through this robotization and computerization more efficient solutions have been brought to the industry and now we are heading to another techno-climax. In this decade we will look for answers to the following questions: What will we consume and how how we will produce them? How will production tools change? Which raw and recycled materials will be used? Will production locations change? All those questions are bringing robots to the fore of the discussion.

I have mentioned about the changes in means of the production promoting in-house production in my previous article “Decentralization of Production and Customization culture”. Also my cowritten academic paper with Eric Watson “Impact of Technological Trends: Scenario Planning the Next Technological Paradigm” aimed to project the possible scenarios. Though in this article I am going manipulate recent technological developments to create a better example in an effort to highlight the importance of preparedness in the next paradigm. Recently, GE has drawn attention to a new industrial revolution arising from rapid prototyping and customizable manufacturing in its advertisements.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gr5ZMxqSCFo

The construction of this house started with CAD (Computer Aided Design) for design before being subjected to 3D component printing and finalized with automated robotic assembly. The best visual example of this final step, a “robotic orchestra” would be Tesla’s Fremont factory. It uses multi-functioning robots which replace the traditional “assembly line”. Despite these great achievements, several problems still remain unaddressed: object recognition, robot communication, and movement.

Consequently, after research I discovered that these problems are tied to the robot’s geometric location. After calibrating a robot’s arms to a specific geometric location in its reachable area any task such as placing an object or welding becomes easy and repeatable. However, changing its location (the constant of the equation) is impossible to do while maintaining the ease and repeatability of the action. Tesla’s factory reflects this where robots do not walk around but hand in their finished materials to automated carts to be moved to the next robot.

GE’s video above takes a step further towards solving this issue by having a robot sliding on a rail (linear unit). A more mobile solution is achievable with a mapping device using technologies such as GPS, an object recognizing camera, or sonar i.e. KUKA’s SLAM method (Simultaneous Localization and Mapping). Through this latter method, laser scanners are used to draw a map and previously saved tasks such as adding bricks can be carried out. This still remains an impractical solution however, as the robots are still lacking of natural object recognition and adding any other task requires detailed calibration.

Evaluating the current level of technology we can recognize general splits into two different directions; efficiency and adaptability. Fields such as manufacturing and engineering use methods to find the best automation ratio by placing robots to the most suitable locations using CAD software like Autocad Plant Design to have the most efficient production. A downside to this method is that adaptability is traded for efficiency. The plant becomes extremely expensive to redesign after the initial configuration restraining alternative production methods and consequently innovation becomes hampered. Semi-configurable methods such as the KUKA robots used by Tesla provide adaptability to the manufacturer who constantly introduces new technologies. As a case and point that’s why a drive system change from single to dual motor in Tesla’s Model S becomes possible. More interestingly Tesla’s Fremont factory can produce different models of cars one after another.

There exists an additional factor to consider, the time horizon. This factors into the balance between efficient production and adaptability. Innovation and creativity reduces product life cycles and with accelerated demand side production reshapes itself with flexible methods. Hence extreme adaptability is still unachievable where robots produce with perfect movement. Accordingly several categories will define the future types of production, indoor, outdoor and difficult conditions i.e. space plants.

Nowadays we are achieving supreme methods in indoor production but outdoor production lags behind as infrastructure remains unfeasible. A practical solution might be having a localizing network using torch like mapping devices integrated into flying drones. Through this, a potential plot of land becomes “digitizable” and consequently manageable. Production robots might navigate this now manageable land on wheels, slidable roller coaster rails (as image one) or more interestingly they can walk as spiders with locking arms (as image two).

Progress in both outdoor and difficult conditions opens avenues for grand ideas. A colony on Mars? More than likely this will be achievable in the near future. This will be aided by leaps in artificial intelligence and robot learning. As long as a robot recognizes the terrain and the target design is consistent, a new level of crowdsourcing rises! If any one robot develops a task calibration that can become useful to the others than the robots can connect to a network where tools, projects and objects will be uploaded using patches.

So how far away are we? Some trade policies still regard labor as a factor of competitive advantage. Sooner or later however, we are heading to a direction where machinery will replace human labor. Through this labor will cease to be a competitive advantage and the trend to outsource will likely be replaced by greater vertical integration. In other words, making becomes more attractive than buying because of dynamic production (switching methods and customizing products) and a steeper learning curve. As mentioned in “Chasing Innovation” creative minds gain more importance and rise as a source of comparative advantage while promoting cheap labor becomes insignificant. Liberalized markets will achieve their own standards to a certain degree or they may be adjusted themselves through the price mechanism. However, some countries will achieve greater success through coordinated and centralized centurial policies of adopting and encouraging new production methods. As highlighted previously, robots will have larger roles in production in the future. Therefore benchmarking technological patterns will help policy makers and managers to understand futuristic trends in order to create greater achievements. Simply put, it helps us to envision the future’s paradigms. Although this article has taken everything as a given beside the price mechanism, a creative ecosystem will require detailed planning and achieving higher standards will define the leaders of tomorrow.

Drawings by the author and featured Image by Curtis Simmons.

What Goto’s Murder Means for Japan and East Asia

On January 31st, various news outlets reported that a video showing the murder of Japanese journalist Kenji Goto had been released by the Islamic State (IS). A similar video had been released a week earlier purportedly showing the murder of Goto’s friend, Haruna Yukawa. These events followed negotiations between the Japanese and Jordanian Government’s with the IS over the release of prisoners. Negotiations between Japanese officials and the IS are currently being reported to have broken down following demands for a US $200 million ransom. In the video released, a member of IS addresses the Japanese government, saying: “Because of your reckless decision to take part in an unwinnable war, this knife will not only slaughter Kenji, but will also carry on and cause carnage wherever your people are found. So let the nightmare for Japan begin.”

Within Japan, government officials have begun to debate the nature and role of Japan’s international activities. The result of these debates among interests holding contrasting views of Japan’s role internationally come at a time when Japan’s identity as a nation is itself in flux. Abe and other nationalist politicians have struggled to convince the Japanese public of the need for changes to Article 9 of the constitution, where the country has renounced war and the threat of force as a way of settling international disputes, and in convincing the public of the need for increasing interaction with foreign affairs. Rather, the Japanese public remains much more concerned with the economic prospects of the country and remains skeptical of any gains that could be made through the new direction proposed by Abe. However, given concerns over the changing balance of power in the region, Abe has been able to find limited success in winning enough support to strengthen the Japanese Self Defense Forces and in increasing funding and logistical support, including arms sales, to allies.

The murder of Goto thus occurs at a potentially opportune time for Abe in terms of his policies. Pictures have shown Japanese citizens around the country holding signs stating “I am Kenji” serve as evidence of the potentially fertile ground in public sentiment. If he and other conservative politicians are able to channel public sentiment to their advantage, they may gain support for further increases in military capabilities and a stronger foreign policy. Such support may find support among Japan’s largest ally, the US. The US has already made limited, although sometimes conflicting, signs of support for a Japan that is more assertive politically and militarily on the international scene. Abe will have to move quickly and lay out his justifications for pursuing a more assertive path convincingly to win over domestic support. If he does so he will likely cite Japan’s inability to respond to such a crisis militarily as a need for legislative change to the Japanese constitution. Already, opposition politicians such as secretary-general of the Democratic Party of Japan Yukio Edano, presumably citing Abe’s prior decision to pledge support to those who oppose the efforts of the IS, have questioned the wisdom of potentially “giving the other side an excuse”. Such sentiments are likely to be widely shared among a population extremely wary getting involved with foreign entanglements. Despite this, the changing realities of the world will inevitably force a change in Japan’s foreign policy posture. Whether the tragedy of Goto’s murder will serve as a catalyst for Japan to embrace these new realities remains to be seen, but for now it would appear that Japan will have to face these new realities sooner rather than later.

A Needed Inquiry: Interview with The Hon Michael Kirby

Note: The following interview was published in the Yonsei Journal of International Studies Vol. 6 Issue 2 and can be found online at their site. The Commission’s full report can be found at the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights.

A NEEDED INQUIRY

Interview with The Hon Michael Kirby AC CMG

Chair of the Commission of Inquiry on Human Rights in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea

Established in 2013 by the United Nations Human Rights Council, the Commission of Inquiry (COI) on Human Rights in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea has provided new and valuable information to those concerned with the situation inside North Korea. Through the conducting of public hearings in Seoul, Tokyo, London and Washington D.C., the commission collected information and released a report in February 2014 which detailed many crimes that had occurred within North Korea, including crimes against humanity. The Hon Michael Kirby, former Justice of the High Court of Australia, was appointed to lead this inquiry. During a recent visit to Yonsei University in Seoul, Editor in Chief Eric Watson was able to interview The Hon Michael Kirby.

Eric Watson: How did you become involved with the commission?

Michael Kirby: I was at a conference of statisticians in England. I was asked if I would allow my name to go forward to become a member of the commission. After reflecting on this with my partner I agreed and a few weeks later I was notified to this commission as a chair. I suspected the background to it was my earlier work in the 1990s as special representative to the secretary general of the United Nations for Human Rights in Cambodia. That was dealing with human rights in a very vulnerable country at a vulnerable time with respect to the Khmer Rouge regime. I believe that this may have influenced the decision of the United Nations human rights council and the high commission for human rights to advance my name.

Eric Watson: Had the previous work in Cambodia benefited you during your work with this commission?

Michael Kirby: Yes it had. As I was the special representative of the secretary general my job was to go on mission to Cambodia to investigate aspects of human rights in the country, to express the good and the bad that was happening, to report them to the human rights commission as it then was in Geneva and the third committee of the general assembly in New York. It therefore gave me experience in the UN special procedures, specifically special procedures for human rights. I also insisted that I take a very active part in the writing of the reports as the special representative. In fact, I wrote all of the reports as a special representative. This was not feasible in the case of the DPRK report, but I weighed every word in the draft and made many suggestions and substantially the report reflects the input of the commissioners. It is not a bureaucratic report that has been written by others, into which the commissioners had little say. In fact, all of us contributed significantly to the style and content of the report. I believe the report on the DPRK is one of the most readable reports of the UN in recent years.

Eric Watson: Certainly it is extremely readable, and I believe you mentioned cutting down some parts to make it that way. However, it still remains very strategic in its use of language.

Michael Kirby: Related to that is the fact that we used the quotations from the transcript of the witnesses’ oral testimony to the COI, which means that the report has a great vividness. It speaks in a very direct way from the viewpoint of the witnesses. It tells the stories of human rights deprivation and the nine headings of the mandate of the COI. All of this adds to the sharp- ness and readability of the reports contents.

Eric Watson: In creating the mandate, what was the process to decide these nine headings and the scope of the COI?

Michael Kirby: The mandate had been decided before I was appointed and was determined by the Human Rights Council. I believe it grew out of the debates between the supporting member countries and the international civil society organization that were active proponents of the creation of a special COI. These international organizations included Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, the International Commission of Jurists, and other international bodies based in Geneva that work around and with the members of the human rights council.

Eric Watson: How did your previous impression and knowledge of North Korea and its regime impact you during your work?

Michael Kirby: I had no great knowledge of North Korea beyond the knowledge of an informed layperson who reads the Economist and is therefore kept up to date with developments in North Korea, but not as a specialist. I could therefore approach the North Korea investigation in a highly professional way as a person who had spent 34 years as a judge, investigating a whole multitude of issues both big and small, at different levels. It was good training for report writing and for the analysis of issues. People ask me, “How was I able to cope with the stress of the Human Rights stories that were told to us by witnesses?” To be completely honest, I didn’t find it that difficult because for most of my life I had been dealing with stories of many wrongs that had been done by one person to another or one institution to another. Therefore, it takes a lot to cause emotion, in a raw kind, on the part of a person like me. In that sense, coming to the issue of North Korea as a person, not an expert, as a person who has professionally for decades been analyzing problems I was able to address the issues of North Korea with a great degree of dispassion. I did not approach it with hostility to North Korea. I did not know enough about North Korea to feel hostile toward the regime. I had curiosity. Even at the end of the inquiry I did not have hostility to North Korea, I just reported the human rights abuses that had been described and that this commission had found had occurred. This was exactly what we were asked to do.

Eric Watson: This use of testimonies is unique. What was the motivation to make these testimonies public and to host them online for viewing?

Michael Kirby: First of all, my experience was in a common law country. In such countries, it is common that these inquiries are held in public. This may be an aspect of general attitudes to transparency or it may be simply a long tradition that has been followed. It does tend to add to cost and time, but it serves a role as an educational process for the community involved. It also allows those making the decisions to be themselves the subject of judgment and scrutiny. There was an additional consideration in the case of North Korea. They did not permit the COI to enter the country despite the resolution established by the Human Rights Council that urged them to cooperate. Therefore, we had the risk that our inquiry would be disrespected because we were not able to enter North Korea. The way to resolve that risk was to ensure that we proceeded in a fair process and that a wide audience could scrutinize the witnesses. Since there is not a wider audience than those that have access to the Internet, we decided it was useful and wise in the circumstances to put the testimony online. This was as long as the witnesses consented and that we judged that there was no risk to them or their families in North Korea. I believe that our decision was vindicated and that the process of the public hearings was a definite plus to methodology of the COI. I believe it is also likely that in the future the UN COI’s will in many cases be conducted in public. It fulfills the information gathering purpose, it stimulates interest, it raises expectations that something will be done, and finally it is more transparent and therefore a more modern way in which to gather evidence.

Eric Watson: In post-apartheid South Africa there was a truth and reconciliation commission. It has been noted that some of those who had been victimized found in a sort of healing or redemptive quality to the public hearings and discussions. Did you find any sort of similar comments from those who gave testimonies? What was the general feeling from some of those who gave testimonies?

Michael Kirby: In a rather formal way, we did not have a lot of contact with the witnesses outside the hearing room of the commission. Therefore, I haven’t had the benefit of reflection by them on their experience from their point of view. Perhaps this displays the attitude of someone who worked for 34 years as a judge. I didn’t tend to meet people before or after they gave testimony. There is an element of remove and independence from the witnesses. We were not working closely with civil society organization. We simply heard the testimony, analyzed it, and then reported on it. It will fall to others to talk to the witnesses and see if it found it redemptive. What was most striking about the witnesses was that like a lot of holocaust witnesses, they gave their testimony in a very low-key, matter of fact way. They did not appear, with perhaps one or two exceptions, emotionally charged or furious or hostile with the DPRK. They were simply recounting some horrible experiences in their life, and on the whole doing so in a very restrained way. Sometimes they would acknowledge aspects of life in North Korea that were favorable to North Korea. This helped to accept his or her testimony, as someone who is simply a hostile witness normally wouldn’t do this.

Eric Watson: In the report, there was an intentional distinction between crimes against humanity and genocide. The commission stopped short of saying this was genocide, but noted that there were grounds for further investigation. What was the thought process behind this?

Michael Kirby: This can be found in the report. The commission was not entitled to decide that genocide had been proved without regard to the technical definition of genocide in international law. The Genocide Convention substantially provides that technical definition. The genocide convention was negotiated in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War and therefore reflected the concerns of genocide that had came to the fore after 1945. Those concerns related mostly, but not only, to the Jewish population that had been exterminated in concentration camps established by the Nazi regimes in the occupied territories of Europe. Therefore, the Genocide Convention defines genocide as the extermination of a population or part of a population by state policy with reference to the ethnicity, nationality, race, or religion of the group in question. In the case of the DPRK, the main rea- son between the extermination of portions of the population of North Korea was not race or religion. It was rather, actual or presumed, hostility to the politics of the regime. Therefore, the grounds of the violent killing of portions of the population did not fit comfortably into the definition of genocide as expressed in the Genocide Convention.

A question then arose as to whether the commission of inquiry should consider that the modern definition of genocide had expanded somewhat form the definition in 1948 in the Genocide Convention. There were arguments both ways on this issue. On the one hand, the convention is a very important document. Genocide is an extremely significant international crime and therefore it should advance to a more modern appreciation to include political genocide. On balance, the COI considered that it should adhere to the Genocide Convention definition, subject to one matter that I will mention. It therefore concluded that genocide could not be found, at least not found on the standard of proof that was accepted by the COI. Namely, the standard of proof that the presence of reasonable grounds for concluding the crime had been made out by the testimony.

There was one subordinate question that arose, which arose out of the fact that a portion of the population had been radically reduced by a reference to religion. The Christian population of North Korea at the time of partition was approximately 24 percent, roughly the same percent as the current Christian population of South Korea. At the time of the commissions report, according to the statistics of the DPRK, the Christian population is at 0.8 percent. The question arose as to whether this was due to extermina- tion or due to the discouragement of religion by communist ideology, which declares that religion is the “opiate of the people”. In other words, some- thing into which people are seduced. This is of course not rational. As we could not definitely decide this question and did not feel we had reasonable ground in favor of finding genocide we ultimately concluded that genocide should not be found by the COI. Additionally we had consulted international scholars, including William Schabas, who is a world scholar on the issues of crimes against humanity and genocide. The important point he made to us was the we should not look to genocide as the international crime equal to the “gold standard”, feeling that in someway we had fallen short of the most serious international crime because we could not find genocide as an established crime in the case of North Korea. He points out that crimes against humanity are themselves extremely serious international crimes and therefore there should be no feeling of any obligation to press further to an equally serious crime of genocide. That being the case, we did not have to press our conclusion that the crime of genocide had perhaps advanced beyond the definition of the Genocide Convention. It was enough to find that crimes against humanity, which we did, and that is where we left the matter.

We did indicate however, that the opinions of the three commissioners, that genocide might have indeed advanced to include political genocide. That is a matter that should have further consideration by the international community. International crimes can expand in content; however, great care must be adopted in a very serious crime like genocide. This is so you do not push it beyond which it can legitimately carry.

Eric Watson: What do you hope this report provides for those working on the human rights situation in North Korea?

Michael Kirby: First and foremost it gives a voice to the victims and people who have been found to be probable victims of very serious crimes against human rights or crimes against humanity. Second, it gives respect to the international human rights organizations which have been supporting and listening to those victims and vindicates their efforts over the years. Third, it compresses into one document a huge amount of knowledge and expertise that has been compressed to about 400 pages. People spend their whole lives studying North Korea, and most people do not have time to consider every aspect of the crimes in North Korea. Now, in a relatively short space, there is a complete review of the crimes that we have found on the nine headings that were provided by the Human Rights Council to the commission. Therefore, the greatest value is that it brings knowledge in a com- pressed form of a very wide range of crimes, and a huge amount of information to a very large audience. It is available online, the public hearings are online, as are the transcripts in multiple languages including Korean. The challenge now is to get the report and the background information into the hands of people in North Korea. The people of North Korea have a right to know what the United Nations has found in respect to human rights in their country. The government of North Korea should make that available to them. The commission constantly requested access to North Korea and has indicated it has prepared to go to North Korea to justify this to the regime and to answer questions. So far, that invitation has not been taken up but the offer still stands.

Eric Watson: We know that China has in instances opposed sanctions against North Korea. Do you feel that this report will put pressure on China and its use of veto power in the Security Council?

Michael Kirby: China is very prudent in its use of veto power given to it as one of the five permanent members of the Security Council under the charter. In the whole history of the occupation of the China Sea by the PRC, China has only used the veto ten times. Including in the most recent instance of the suggestion that Syria should be referred to the International Criminal Court. That is a very small number in contrast to the Russian Federation and the US, which has used the veto power many more times. So, it can’t be assumed that China will use its veto power, and in any case it is a decision China will have to make. It will have to face the people of the world and the pages of history. Already in blogs in China, in the new openness of China, are beginning to ask why their government is not supporting the actions of the UN in respect to the horrible acts reported on the part of North Korea. It is a question of China’s assessment of itself and of China’s assessment of its role as a permanent member of the Security Council. It is one of the coun- tries with the gateway keys to the responsibility to protect. The responsibility to protect exists in international law, at least in cases where the crimes are crimes against humanity or genocide, and the country concerned will not protect its citizens, such as North Korea.

Eric Watson: One of the findings was the poor welfare of children, specifically those that participate in the mass games that are a tourist draw in North Korea. What is your personal opinion of tourism toward the DPRK?

Michael Kirby: On the whole, I think tourism is a contribution to human peace and human rights. Many countries try to control what tourists do and where they go. No country is as emphatic in its control as North Korea. Therefore people who go to North Korea have to understand that they are going to a country where they will not be able to just wander around and visit where they would like to. They will be under the control of their guardians who watch their every move and ensure that they do not make contact with ordinary Korean people. It is not really tourism, as we would normally understand the word. I believe the mass games stand as a case apart. We found evidence that the children that participate in the mass games do so at the expense of their education. They are taken from their classes, they have to endure extremely long hours often in harsh weather conditions, all for a relatively short time of glorifying the regime and its supreme leader and the supreme leaders family. For my part, I can see some reasons as to why people would visit North Korea as a tourist. It would give them some idea, and perhaps some opportunities to express their beliefs, and express the solidarity of the international community. But, at the moment, I do not think I would visit the mass games. They might have magnificent choreography, but so were the Nazi parades. It isn’t an attribute of a free society to have thousands of people and thousands of school children engaged in a mindless set of exercises where the only beauty of it is that they are all in locked step doing the bidding of the supreme leader.

Eric Watson: During your time in Seoul, you met with researchers and public officials. What have been the responses from these individuals when discussing this report with you?

Michael Kirby: I think there is a lot of understanding of the report and of the report’s addressing, acknowledging, and condemning of the human rights abuses in North Korea. There is an anxiety in South Korea as to whether such condemnations will set back the cause of unification. There is a feeling in South Korea that many of the problems of North Korea will be solved only if the two Koreas can be united. After all, they were united for thousands of years before a line on a map divided them artificially. To say, not by the will of the Korean people. So there is an understanding of the need to identify human rights abuses, but there is also an anxiety. That conflict within South Korea is symptomatic of political dividedness in the political landscape of South Korea. It is a difficult issue, but it is important to realize that no reconciliation and reunification can in practical terms be secured, accepting the terms of North Korea, unless there is a foundation of truth. That is, unless there is a foundation of description of serious international crimes and the acknowledgement of those crimes, and the accountability of at least those who are most to blame for them. Without that foundation, any form of unification would be extremely fragile because it would be built on thin ice.

Eric Watson: Do you have any comments for citizens of the world now that these testimonies and report are public? What would action would you like to see happen?

Michael Kirby: First, I hope that the commission’s report does not simply gather dust as is often the case with UN reports. Second, I hope that the momentum that has been built up by very widespread publicity of the re- port will continue. North Korea has been an expert at avoiding publicity of their wrongs and it is important that the world knows, and addresses these wrongs that have occurred over decades to the people of North Korea. Third, I hope that the field office that will be created in South Korea will become a place where victims can go and have their stories recorded. Hopefully these stories will become in due course possibly part of the brief for the prosecutorial services of the ICC or other judicial tribunals, and certainly for the history of the Korea people it is important that this chapter is recorded and kept for posterity. Only those who recall and learn from the lessons of history will avoid repeating them. Finally, I hope that the case of North Korea will once again illustrate the importance of universal human rights. The ambassador for North Korea said that they have a saying in Korea, “mind your own business”. Human rights are the business of the whole world, and it is important that we constantly acknowledge that and renew our conviction. We must do something when we are informed of serious crimes, particularly crimes against humanity and genocide.

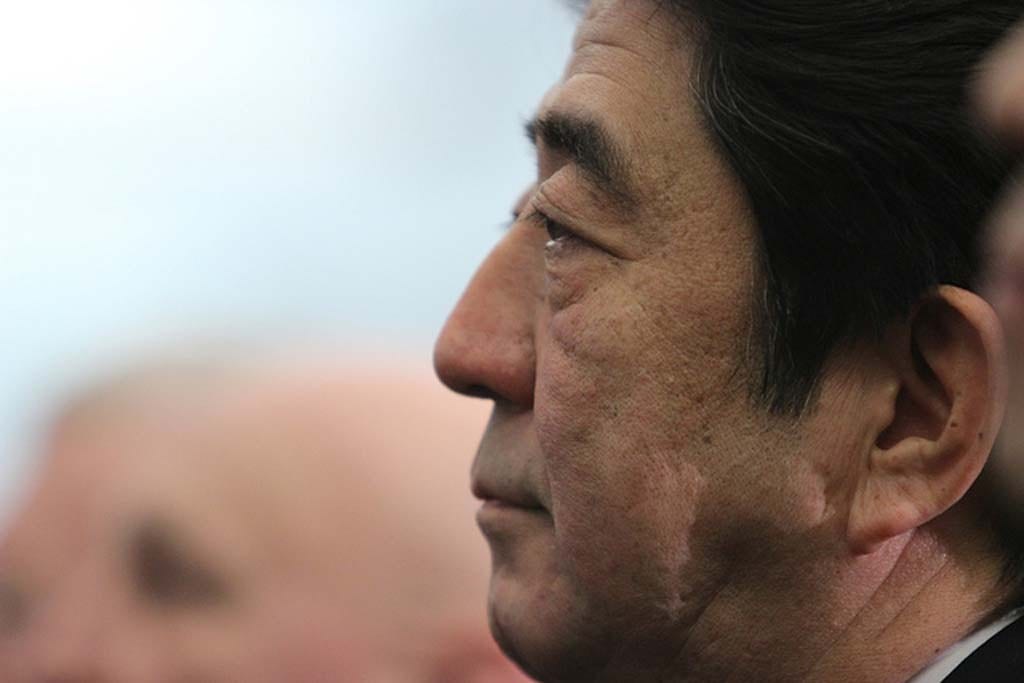

US Amb. Lippert’s Statements and the State of US-ROK-JPN Relations

Earlier today, January 27th, the Korea Times reported that the US Ambassador Mark Lippert reaffirmed the US’ support for the Murayama statement. The Murayama statement, released in 1995 by former Japanese Prime Minister Tomiichi Murayama apologizing for Japanese actions towards its Asian neighbors, is often pointed to as the official apology for Japan’s wartime aggression. Lippert’s remarks follow recent statements by Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. Abe seemed to indicate in a recent interview that on the upcoming 70th anniversary of the end of WWII his statements may differ from the wording used by past Japanese prime ministers.

At a time when the relations between Japan and Korea are as poor as they ever have been since establishing official ties, Abe’s remarks immediately drew the attention of the US. A close ally to both, the US relies on both countries for its presence in Asia and has so far preferred to avoid applying any direct pressure to the two countries in regards to their territorial and historical disputes. Lippert’s statement appears to be an indication of a heightened sensitivity to provocations that would threaten the uneasy relationship between the two democracies. Lippert seemed to try to preempt others from drawing this conclusion however, stating:

|

“Our [the US] role is not to mediate, to play a formal mediation role, but to encourage two great nations with two democratically elected leaders to come to a resolution on this.”

|

However, the fact that a statement of US support for the existing wording on the issue from an ambassador was seen as necessary would seemingly contradict the assertion that the US was not taking an increased interest in the trajectory of the two countries disputes.

The US is perhaps seeing its position between the two countries deteriorating and attempting to prevent further slipping. Recently, South Korea has signaled willingness to pursue a different course in dealing with North Korea, much to the perceived chagrin of the US. Japan’s position in relation to the US in Asia has also shifted, with its power in the region in decline causing doubt of the long term prospects of the US’ “cornerstone” in the region. In this context, Lippert’s statement can be read as an attempt to hold two increasingly independent countries together with the US as the center. Unfortunately for Lippert and those in Washington, attempting to do so without being willing to take the role of “mediator” may not be enough.

Chasing Innovation

Urbanization has been the engine of modernization in Europe. For most citizens today, every event from birth to the grave including education, marriage, work and leisure, occur in cities. Cities are mirrors of cultures and regimes.

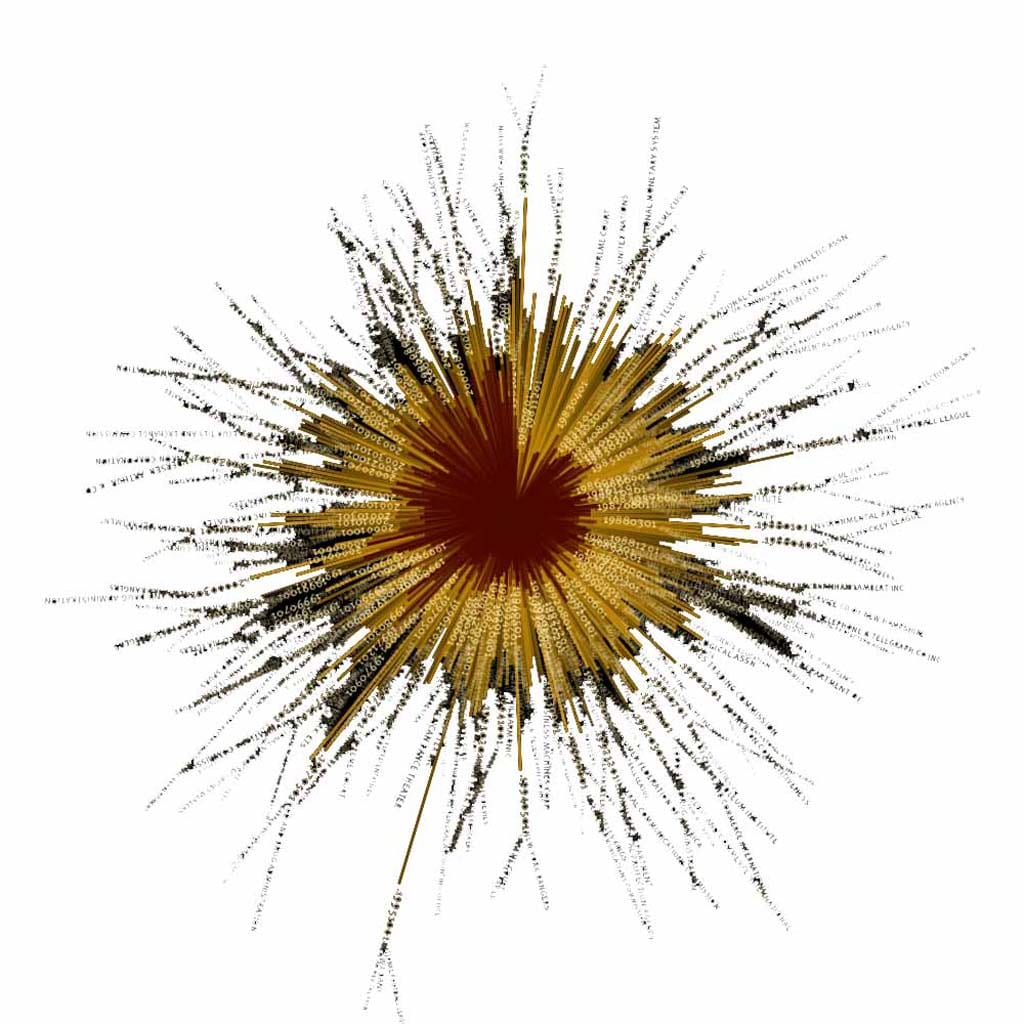

McKinsey’s report entitled “Urban World: The Shifting Global Business Landscape” predicts the changes of the major cities in the next decade. According to the report, there are 8,000 companies that account for 90% of the total world GDP and third of those companies are located in 20 major cities that generate 40% of their revenue. McKinsey’s forecast shows that by 2025, there will be 15,000 companies to have headquarters in 330 cities, and 40% of these companies will be located in emerging economies. Additionally, according to UN’s estimations, between 2010 and 2050, over 40% of the world’s population will be living in cities.

Other studies, such as the UN Habitat: State of the World’s Cities 2012/2013, present a prosperity framework which tries to achieve equitable distribution; where poverty is reduced, minorities have rights, genders have equal participation, energy is used efficiently and the quality of environment is increased.

The UN also presents some facts regarding the rise in productivity with urbanization and they find two general categories of factors that affect productivity: external factors that give comparative advantage and production factors. The first factor discusses economies of scale and agglomeration economies (matching, sharing, learning); and the second factor discusses technical efficiency, institutional scaffolding, quality of life, learning-based efficiency and vision. The UN also finds the perfect mix of policy-related factors in which management and planning are effective, ruling is decentralized to institutions, local officials are elected, and a business environment is favorable. Some cities already have these factors that can also be implemented in emerging cities. However, while some regions might fail to follow technological reforms, which shift labor structures with industrialization creating new classes as engineers, a more significant problem is the adaptation speed, which varies among different cities.

Cities are competing economically to attract more financial investment, and in turn we have started to live in hubs for the interests of a few dominant companies, not necessarily for ourselves. As a result, we are heading to a more liberalized global system where urban ecosystems might differ from one location to another. Therefore, the question that arises is whether states should govern as they do today or adopt the city-state model. Hence, marking clear boundaries of cities seem to be an issue that leads researchers to discuss the idea of “mega-regions”.

Mega-regions are integrated sets of cities where labor and capital can be reallocated at a very low cost. In this futuristic outlook, it is safe to assume there will be inter-city and inter-region economies, which will be ruled by the local governments. As a consequence, policy makers are trying to develop “regional governance” mechanisms. People could choose to live in isolated cities with global economic ties and prosperity. Indeed, mega-regions and urban corridors generate regional economies and trigger the evolution of new patterns of economic activity.

Jeremy Rifkin’s book, Zero Marginal Cost Society, tries to predict the rise of the global collaborative commons and the eclipse of capitalism with an Internet of things. Hence, the future can also occur differently than previously discussed because some companies and even countries may have problems to chase the innovation. The biggest problem occurs if innovation is directly related to the labor mechanisms. The distribution and redistribution becomes almost impossible if you cannot be on the cusp of innovation. As a hypothetical example, in the next few years, production may occur in unified factories, which will make everything efficiently. Tesla Motor’s Fremont factory already shows several differentiations from what is known as “Fordism”, with cars no longer assembled on the lines but by multi-functioning robots switching three different functioning arms to produce the car from top to bottom. Tesla’s robots’ key differentiating factor is their “brain”, which, while versatile, still requires someone to teach them how to screw or weld parts.

Several other companies, including Google, are researching machine learning. Soon, production will be carried out by multi-functioning collaborating robots combined with artificial intelligence, resulting in a replacement of the majority of the labor force. 3-D printing technology has already revolutionized production methodology. Now people can design a product, print, test and if it seems successful, they can order mass production. Therefore, creative environments have become a major element of urban ecosystems. The UN lists factors that are affecting the creative environment of a city: locational advantages, knowledge networks, culture, economic environment, organizational factors and state/government interventions. In consequence, several cities will have advantages over others, and only the most creative environment will have standout success.

According to Andrew Goudie, R.J. Johnston, Peter. J. Taylor, Michael Watts, Eckart Ehlers and Thomas Krafft, mega-cities face five different changes: geo-ecological, geo-economic, geo-social, geo-cultural and geo-political. The top 20 major cities are facing all of them. These changes have negative and positive impacts. Frauke Kraas lists some major benefits of mega cities including: economic intersections, agglomeration economics, growth of productivity, growth of creativity and synergic innovations. Therefore, various problems, such as loss of social coherence, social disorganizations, injustice, and loss of representation, should be solved.

Thus, to have a more balanced worldwide economy, inter-city developments should be achieved before chasing innovation becomes impossible. After all, people are becoming migrant and more digital, and are likely to choose the best opportunities for themselves. It is clear that liberalized cities’ market mechanisms will govern the future and the transformation and adaptation may create more wealth distribution problems worldwide. Nevertheless, these movements may create advantages for some cities over others where every production or innovation occurs only in certain places by certain people.

A Tantalizing Glimpse of the Social Web in the Future; When Everything is Connected

Imagine yourself chatting with your home before you leave the office. Your home control panel will immediately communicate with an oven and a cooktop to prepare dinner and activate the washing machine before you arrive home. Your vacuum will check the condition of your carpet and clean it. When you are stood up on a date, your home will respond and recommend you food. Your home appliances will gear up for a warm welcome to cheer you up. Once you walk into the house, your favorite music and TV program will already be on along with a welcoming message.

This is what Ericsson believes is the upcoming society. In years to come, wireless communications will progressively become part of the fabric of everyday life. Tiny communication chips and sensors will be embedded everywhere, weaving themselves into dense digital meshes. Internet-enabled objects will chat with one another by transmitting massive volumes of data; which once collected, will be processed and analyzed in real time for a variety of applications, creating seemingly endless opportunities for business.

This may sound like a futuristic movie story line, but evidence demonstrates that this blue-sky dream is becoming real. A group of university students in Korea, for instance, developed a “smart pot” that controls lights and waters plants via a smartphone. Other innovations already exist such as a fork that vibrates when you eat too fast and transmits data to an accompanying app that analyzes your eating habits; and a pill bottle that glows, beeps and calls you on the phone when it is time for you to take your medication. In Japan, vending machines can recognize a customer’s age and gender and accordingly alter the message they display.

The concept of Internet-connected objects that communicate with one another has been floating around for years, often known as the “Internet of Things” (IOT). According to Cisco’s report, the number of connected devices was 12.5 billion in 2010, and will increase to 50 billion by 2020. According to IDC, an American market research firm, the market size of IoT is expected to be $8.9 trillion in 2020.

Sensing the opening of new business opportunities, big technology firms jumped on the bandwagon. Samsung announced a smart-home platform that enables people to control home appliances via a single App. Google spent $3.2 billion to purchase a thermostat developed by a startup called Nest. This smart thermostat is programed to learn a homeowner’s schedule regarding heating and to automatically control home temperature. Google believes that the acquisition of Nest allows it to make a quantum leap in the upcoming battle of home automation business.

Governments have also showed their interests in the market. They are spending large amounts of money on smart infra-projects and setting the industrial development of IoT as a priority. IoT assumes a central role in the EU’s “Digital Agenda” for instance. In 2009, the EU revealed its 14 action plans for IoT. In 2012, China approved IoT as one of the national strategic industries in the 12th five-year development plan. The Chinese government is planning to spend five billion Yuan to promote the industrial development of IoT. In Japan, the government formulated the “I-Japan Strategy 2015” which includes a plan to develop sensor network-based machine-to-machine (M2M) technologies.

A smart web of internet-connected things may sound amusing to our ears, but what is rarely mentioned about its future is that interconnected chips and sensors make computers vulnerable to hacker attacks; which raises privacy and security concerns. In such a hyper-connected society, governments may also turn into a digital leviathan with absolute access to information, putting citizens under secret surveillance, to mirror Orwell’s “1984”. Governments are not likely to be the only snooper to fret about. Firms will strive to collect and store data about people, and thereafter relentlessly send out massive personalized ads. Individual ability to tackle these foreseeable problems appears to be extremely limited.

Even if you overcome these structural problems, sweep aside privacy and security concerns and build an interconnected paradise, the automation of industries may wreak havoc on the employment prospects of less-educated workers. The IoT is likely to replace low-skill jobs with machines or computer algorithms and render millions of manual jobs redundant. As Braverman, an American political economist, pointed out, a new technological change is intimately related to changing patterns of inequality, deskilling the labor force to lower production costs and increase the wealth of business owners. Therefore, an interconnected digital utopia could be a nightmare for less-skilled workers and provoke a neo-Luddite reaction.

What can be done to prevent a worst-case scenario? Hardware/software engineers should incorporate better privacy protection into their products, and manufacturers and network service providers ought to keep more watchful eyes on their networks to ward off cyber-attacks. Furthermore, governments must establish legal frameworks to ensure transparency about what data should be collected, and design a social policy to mitigate the digital divide. These aforementioned solutions are well known, yet difficult to be implemented. Hopefully, this article leaves you with more questions than answers, prodding you to envision the glimpse of a future society, recognize potential problems and wonder why it has been difficult to tackle these forthcoming problems.

Coping with Demographic Realities: The Case of Kawane Village

Trends in urbanization are often accompanied by even more significant trends of depopulation in rural areas. Japan presents an extreme case in population changes as in addition to being an incredibly urbanized state; it has one of the lowest birthrates in the World. As a consequence, the care of the elderly who remain in rural areas is of growing concern. Efforts from the Japanese government to date have revolved around consolidating the small rural hamlets into larger administrative units. While this drastically improves the efficiency in fund allocation from a governmental standpoint, the services provided to the residents of these hamlets, who are overwhelmingly aged and vulnerable, has significantly decreased. Previously, funds were allocated to each individual hamlet and decisions on utilization were done on the basis of personal connections. After consolidation, the increased geographical distance of the officers from the citizens meant that those residents who needed services were often unable to promptly or adequately receive them. Consequently, self-organization has become a trending topic of research. Significant difficulty exists in implementation of self-organization however, as trends in urbanization have led to severe depopulation in rural communities. As a result, to date, successful examples of this self-organization in Japan have been scarce. One example however, Kawane village, through its unique experiences, has become a potential model of successful self-organization in Japan.

Kawane village is located a three hour drive from Hiroshima in Western Japan, and consists of 19 hamlets located in a mountainous, difficult to access area. As of the 2005 census, Kawane Village had 623 residents comprising 266 households. Of these households, 153 were identified as being farmers and almost half of the population was aged over 65. The merger with other villages into the city of Akitaka in 2006 created new problems for Kawane. Following the merger, there was an increase in costs related to public services in addition to a decline in the quality of these services. Despite these realities, the residents of Kawane Village have been able to maintain a high quality of life through successful self-organization that started more than 30 years prior.

In the summer of 1972, Kawane village suffered a devastating flood, which consequences were worsened due to the slow and inadequate efforts of the local government. The residents, realizing their disadvantageous location, began to reorganize. An “our village in our hands” attitude grew among the residents, focused on a need for greater self-sufficiency. The Kawane Promoting Association (KPA), previously consisting of only a few households, grew to represent the village and this new attitude. As membership increased, driven by this attitude, the hamlet level traditional organization scheme was replaced by the KPA, which now counts every household as a member. This cross-hamlet coordination also allowed the KPA to become the organizing body of local cultural activities. These cultural activities, including festivals and other activities were previously under threat of disappearing due to a lack of manpower at the individual hamlet level. The KPA now became the body through which coordination across hamlets could occur, mustering manpower and resources to protect these cultural traditions.

The decision to close the Junior High School in 1983 further increased acknowledgement of the KPA’s role as a representative for the village. In addition to being the only Junior High School in the area, the school served as an informal “heart” of the village and its closure would be a severe psychological blow. The KPA, was able to create a plan that was successful in saving the facilities and repurposing them into a community center which would offer services necessary for the aging population. Through this action, the KPA became the de facto representative of the village with the local government despite not having any formal power and deriving its legitimacy solely through trust among its members and its ability to respond to their needs. Consequently, the local government found it more efficient to work with the KPA rather than the individual hamlets. No longer having to negotiate with each individual hamlet for fund allocation, the local government could now negotiate with the KPA directly because of its ability to distribute the benefits most efficiently and settle any disputes related to this role informally. This was in contrast to the unwieldy formal way in which the local government was previously obligated to. In addition, the cost-effectiveness of this arrangement is significant, with only 20% of the revenue of the KPA coming from subsidies.

Kawane Village and the KPA are an example of how self-organization among rural areas provides a viable potential model for effectively dealing with depopulation in these areas. Compared to simple consolidation that is primarily bureaucratic in nature and with benefits solely to the central government, self-organization provides an alternative that benefits both the central government and the vulnerable citizens of the rural areas.

Note:

“The research that was the basis for this article was found through field research conducted by Professor Kim Dool-Chul of Okayama University.”

How to Design a Truly Smart City

For hundreds of years, people have been flocking to cities where jobs, ideas, and wealth are generated. Cities have been perceived as a symbol of opportunities for success, attracting millions of youths and ambitious individuals every year. According to the United Nations’ projections, by 2050, the urban population will rise to almost 6.5 billion, and 64.1% of the developing countries and 85.9% of the developed countries will be urbanized. In response to rising urban population, some countries, such as China and India, have been spending heaps of money to build new cities for the accommodation of mounting city dwellers.

Growing urbanization has caused several problems (e.g. environmental degradation, excessive energy consumption, and traffic congestion). City planners have selected Information Technology (IT) as a solution to some of the urbanization problems as well as a means to promote economic growth. Smart grids, for instance, have been installed to reduce the peak demand of electricity and to conserve energy. The Economist introduced a calculation, which states that if America’s power grid were only 5% more efficient, it would save the equivalent of the greenhouse-gas emissions of 53 million cars. Thomas L. Friedman also claims in his book, Hot, Flat, and Crowded, that smart grids assume a critical role in sustaining people’s lives in the future.

A fleet of governments has been expending large sums of their budgets to transform their cities into “smart” ones. Some have put the building of smart cities on the priority list of their industrial policy. China, for example, has selected 202 cities to pilot smart city projects, according to Xinhua news. Those cities are test beds for the implementation of a new information technology called the Internet of Things (IoT), which connects things to the Internet and provides newfangled services to people. According to Cisco’s guesstimates, by 2020, there will be 50 billion networked things whose Internet usage will outnumber that of humans. IoT-integrated smart systems are expected to enable people to collect, process, and act on colossal amounts of data, and thereby furnish the world’s metropolises with a “second electrification” (the term is coined by Ricky Burdett of the London School of Economics (LSE) to describe the impacts of big data on cities by analogy with those of electricity.)

Yet some see many of the current smart city projects being overhyped, contending that smart systems currently being established in municipalities are, by and large, repurposing of existing, off-the-shelf technology, and force fit into contexts in which they may or may not prove to be useful. For instance, Anthony M. Townsend, the author of Smart Cities: Big Data, Civic Hackers, and the Quest for a New Utopia, argues that Songdo, South Korea’s ambitiously planned smart city, is an example of smart city project failure. Located in reclaimed land, Songdo is one of the world’s largest experiments in urban automation, which is expected to cost $35 billion. The city was designed to offer all-embracing connectivity—for instance, home automation and telepresence. While it boasts skyscrapers with built-in electronic systems, Songdo lacks people. Since not many want to live there, Songdo has been seemingly metamorphosing into a ghost city. This is because the city was created for technology, not necessarily for people. Another failure of smart city project, Mr. Townsend claims, is Masdar in Abu Dhabi, which was exemplified as a city designed for people in Lester R. Brown’s book, Plan B 4.0. The completion of Masdar has been delayed to 2025 at the earliest in part due to a lack of businesses and people who want to live there. The mantra, “build it and they will come”, does not appear to be working properly for these two cities.

The failure of smart city projects offers a lesson, i.e. cities cannot be smart without people. For cities to be truly smart, city designers ought to tackle a fundamental question, “what do people want in a smart city?” instead of “what technology makes a smart city possible?” In her influential book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, the acclaimed urbanist Jane Jacobs argued that “cities have the capability of providing something for everybody, only because, and only when, they are created by everybody.” That is to say, public participation at a grassroots level (i.e. bottom-up approach) is the key to success of a smart city. Technologies, such as smartphones, wireless sensor networks, and open-source platforms, may assist people in designing smart cities for themselves. Yet, they are of little use if people are unwilling to engage. Now your correspondent raises a question for you, “how much are you willing to engage in designing a smart city?”

Wheels Falling off the WTO: Is it high time to write an obituary for multilateralism?

Multilateralism was believed to have returned from the grave, when delegates to the World Trade Organization (WTO) bragged of the Bali deal, the first fruit to be reaped out of the long-deadlocked multilateral trade negotiations in December 2013. The resurrection of the Doha round of international trade talks was indeed quite a surprise to those who already promulgated the end of multilateralism. Doha negotiations, initiated in 2001, were suffocated owing to the conflict of interest among WTO members in intractable issues such as agricultural subsidies, intellectual property rights and trade in services. They also experienced the collapse of talks in 2003 and 2008. In 2012 however, the flame of multilateral negotiations was rekindled as the WTO endeavored to simplify the agenda and channel the focus of talks into “trade facilitation”, i.e. the cutting of red tape in customs procedures, which was predominantly supported by the members. When the Bali package was signed in late 2013, a rosy future of multilateralism was sketched out with optimistic economic estimates—for instance, the Peterson Institute for International Economics forecasted that trade facilitation would generate 21 million jobs, particularly in less developed nations, and could increase developing countries’ annual output by $523 billion, tilting the playing field of world trade to the advantage of underprivileged countries.

The banquet for the revival of multilateralism was soon called off when India, claiming itself as a torch-bearer for Third World countries, scuppered the Bali deal in July 2014. India’s backing-out was due primarily to its “food security” laws and domestic politics. Responding to recent food price fluctuations, India planned to implement a series of policies to ramp up agricultural production via farming subsidies. Such growing subsidies were likely to run afoul of the WTO legal principle—for example, trade-distorting subsidies to farmers in a developing country cannot exceed 10% of the total value of its harvests. Highlighting the significance of food security, India has insisted on a change in the multilateral trading system. Succumbing to pressure, other WTO members were willing to make concessions to India by including a four-year “peace clause” that would have exempted its food security measures from challenges in the WTO. However, the new Indian government was unsatisfied with this offer and halted the Bali deal, demanding a permanent solution for agricultural subsidies in developing countries. It is unfortunate that India’s stiff opposition to the Bali package is likely to deliver a fatal blow to most of the developing countries, as most of the benefits from the trade facilitation deal would be concentrated in impoverished nations.

What is even more concerning is that a continuing failure to reach a consensus on a multilateral trade deal would eviscerate the world trading system and question the WTO’s raison d’etre. Difficulty in gathering a consensus among the WTO members is attributed to the WTO’s “single undertaking” approach, in which nothing is accepted until everything is agreed. In turn, making progress is extremely challenging without resolving some of the inflexible trade issues. Furthermore, the eclipse of the multilateral trade system reflects a shift in the economic balance of power. Flexing their newly found muscle in the economy, emerging market economies (EMEs) are stalwartly voicing their opinions and are often demanding exemptions in negotiations with industrialized nations, which are reluctant to give ground. EMEs also call for protection from each other, China in particular. Limits of the “single undertaking” approach coupled with rising demand from newly emerging stakeholders have outshadowed the prospect of multilateralism and, in turn, have spotlighted regional trade deals as an alternative.

Fatigued by lack of progress on a multilateral deal, many of the rich nations arm-twisted their way with mega-regional trade agreements (RTAs), including a Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and a Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP), blazing an alternative path for trade liberalization. TTP and TTIP, accounting for half of the global trade, aims not only to ensure comprehensive duty-free market access but also to incorporate “21st-century” aspects of “behind-the-border” issues, such as intellectual property, labor and environmental standards and government procurement. Witnessing a shift to a more fragmented world trading system and recognizing difficulties in reconciling with the US-led “behind-the-border” liberalization, countries like China and Russia attempted to entrench their own regional trade blocs. China, for example, has been vigorously pushing various bilateral trade deals. It also participates in the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), whose members are comprised of ASEAN countries, Australia, India, Japan, New Zealand, South Korea and China. Evidently, a growing number of RTAs are apt to serve as a substitute for, not a complement to, multilateralism. This therefore poses an existential threat to the multilateral trading system. Now it is time for us to hearken to Arvind Subramanian of the Peterson Institute’s warning that “multilateral trade as we have known it will progressively become history.”