Imagine yourself chatting with your home before you leave the office. Your home control panel will immediately communicate with an oven and a cooktop to prepare dinner and activate the washing machine before you arrive home. Your vacuum will check the condition of your carpet and clean it. When you are stood up on a date, your home will respond and recommend you food. Your home appliances will gear up for a warm welcome to cheer you up. Once you walk into the house, your favorite music and TV program will already be on along with a welcoming message.

This is what Ericsson believes is the upcoming society. In years to come, wireless communications will progressively become part of the fabric of everyday life. Tiny communication chips and sensors will be embedded everywhere, weaving themselves into dense digital meshes. Internet-enabled objects will chat with one another by transmitting massive volumes of data; which once collected, will be processed and analyzed in real time for a variety of applications, creating seemingly endless opportunities for business.

This may sound like a futuristic movie story line, but evidence demonstrates that this blue-sky dream is becoming real. A group of university students in Korea, for instance, developed a “smart pot” that controls lights and waters plants via a smartphone. Other innovations already exist such as a fork that vibrates when you eat too fast and transmits data to an accompanying app that analyzes your eating habits; and a pill bottle that glows, beeps and calls you on the phone when it is time for you to take your medication. In Japan, vending machines can recognize a customer’s age and gender and accordingly alter the message they display.

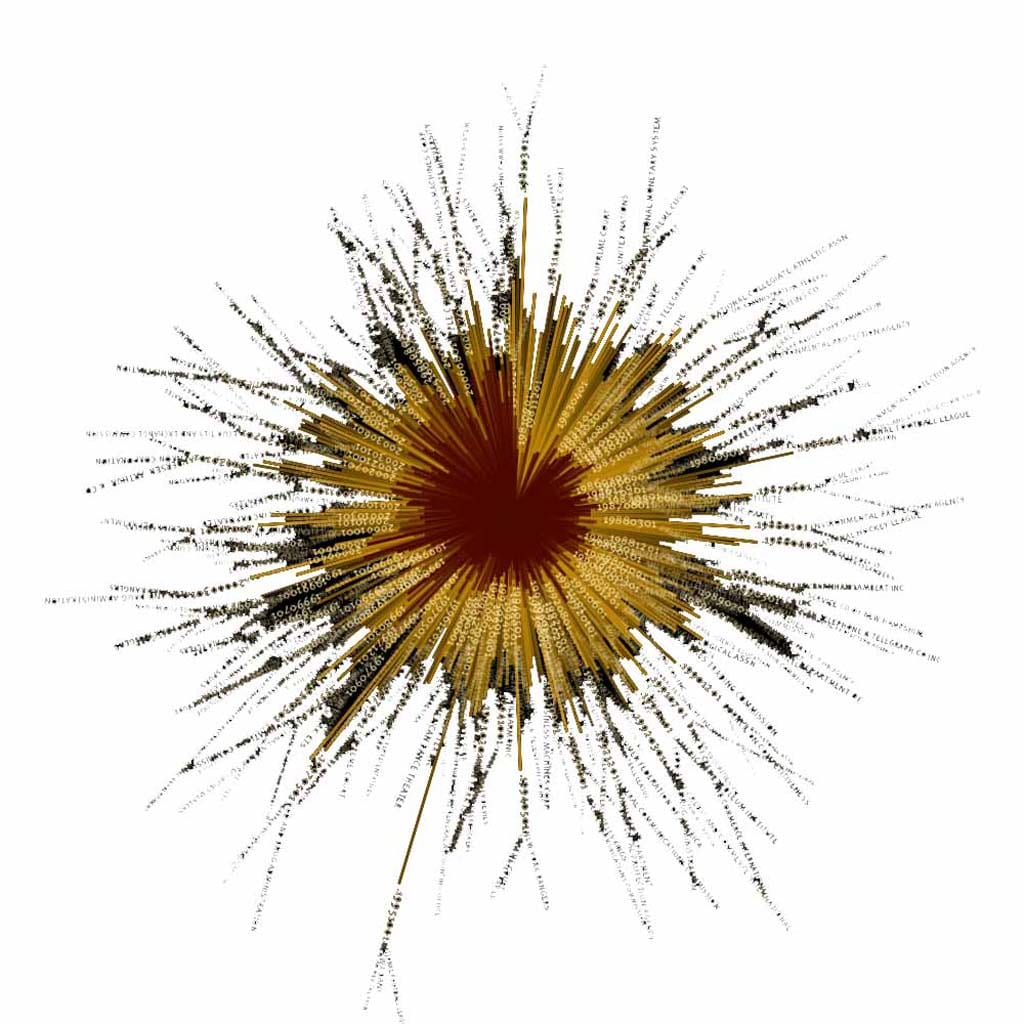

The concept of Internet-connected objects that communicate with one another has been floating around for years, often known as the “Internet of Things” (IOT). According to Cisco’s report, the number of connected devices was 12.5 billion in 2010, and will increase to 50 billion by 2020. According to IDC, an American market research firm, the market size of IoT is expected to be $8.9 trillion in 2020.

Sensing the opening of new business opportunities, big technology firms jumped on the bandwagon. Samsung announced a smart-home platform that enables people to control home appliances via a single App. Google spent $3.2 billion to purchase a thermostat developed by a startup called Nest. This smart thermostat is programed to learn a homeowner’s schedule regarding heating and to automatically control home temperature. Google believes that the acquisition of Nest allows it to make a quantum leap in the upcoming battle of home automation business.

Governments have also showed their interests in the market. They are spending large amounts of money on smart infra-projects and setting the industrial development of IoT as a priority. IoT assumes a central role in the EU’s “Digital Agenda” for instance. In 2009, the EU revealed its 14 action plans for IoT. In 2012, China approved IoT as one of the national strategic industries in the 12th five-year development plan. The Chinese government is planning to spend five billion Yuan to promote the industrial development of IoT. In Japan, the government formulated the “I-Japan Strategy 2015” which includes a plan to develop sensor network-based machine-to-machine (M2M) technologies.

A smart web of internet-connected things may sound amusing to our ears, but what is rarely mentioned about its future is that interconnected chips and sensors make computers vulnerable to hacker attacks; which raises privacy and security concerns. In such a hyper-connected society, governments may also turn into a digital leviathan with absolute access to information, putting citizens under secret surveillance, to mirror Orwell’s “1984”. Governments are not likely to be the only snooper to fret about. Firms will strive to collect and store data about people, and thereafter relentlessly send out massive personalized ads. Individual ability to tackle these foreseeable problems appears to be extremely limited.

Even if you overcome these structural problems, sweep aside privacy and security concerns and build an interconnected paradise, the automation of industries may wreak havoc on the employment prospects of less-educated workers. The IoT is likely to replace low-skill jobs with machines or computer algorithms and render millions of manual jobs redundant. As Braverman, an American political economist, pointed out, a new technological change is intimately related to changing patterns of inequality, deskilling the labor force to lower production costs and increase the wealth of business owners. Therefore, an interconnected digital utopia could be a nightmare for less-skilled workers and provoke a neo-Luddite reaction.

What can be done to prevent a worst-case scenario? Hardware/software engineers should incorporate better privacy protection into their products, and manufacturers and network service providers ought to keep more watchful eyes on their networks to ward off cyber-attacks. Furthermore, governments must establish legal frameworks to ensure transparency about what data should be collected, and design a social policy to mitigate the digital divide. These aforementioned solutions are well known, yet difficult to be implemented. Hopefully, this article leaves you with more questions than answers, prodding you to envision the glimpse of a future society, recognize potential problems and wonder why it has been difficult to tackle these forthcoming problems.